Uncertain whether to get out of the car, Rufus Scales said, he reached to restrain his brother from opening the door. A black officer stunned him with a Taser, he said, and a white officer yanked him from the driver’s seat. Temporarily paralyzed by the shock, he said, he fell face down, and the officer dragged him across the asphalt.

Rufus Scales emerged from the encounter with four traffic tickets; a charge of assaulting an officer, later dismissed; a chipped tooth; and a split upper lip that required five stitches.

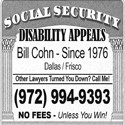

That was May 2013. Today, his brother Devin does not leave home without first pocketing a hand-held video camera and a business card with a toll-free number for legal help. Rufus Scales instinctively turns away if a police car approaches.

“Whenever one of them is near, I don’t feel comfortable. I don’t feel safe,” he said.

As most of America now knows, those pervasive doubts about the police mirror those of millions of other African-Americans. More than a year of turmoil over the deaths of unarmed blacks after encounters with the police in Ferguson, Mo., in Baltimore and elsewhere has sparked a national debate over how much racial bias skews law enforcement behavior, even subconsciously.

Documenting racial profiling in police work is devilishly difficult, because a multitude of factors — including elevated violent crime rates in many black neighborhoods — makes it hard to tease out evidence of bias from other influences. But an analysis by The New York Times of tens of thousands of traffic stops and years of arrest data in this racially mixed city of 280,000 uncovered wide racial differences in measure after measure of police conduct.

Those same disparities were found across North Carolina, the state that collects the most detailed data on traffic stops. And at least some of them showed up in the six other states that collect comprehensive traffic-stop statistics.

Here in North Carolina’s third-largest city, officers pulled over African-American drivers for traffic violations at a rate far out of proportion with their share of the local driving population. They used their discretion to search black drivers or their cars more than twice as often as white motorists — even though they found drugs and weapons significantly more often when the driver was white.

Officers were more likely to stop black drivers for no discernible reason. And they were more likely to use force if the driver was black, even when they did not encounter physical resistance.

The routine nature of the stops belies their importance.

As the public’s most common encounter with law enforcement, they largely shape perceptions of the police. Indeed, complaints about traffic-law enforcement are at the root of many accusations that some police departments engage in racial profiling. Since Ferguson erupted in protests in August last year, three of the deaths of African-Americans that have roiled the nation occurred after drivers were pulled over for minor traffic infractions: a broken brake light, a missing front license plate and failure to signal a lane change.

Violence is rare, but routine traffic stops more frequently lead to searches, arrests and the opening of a trapdoor into the criminal justice system that can have a lifelong impact, especially for those without the financial or other resources to negotiate it.

Click here to read more about risks of driving while black.