Part II of II

By Lamar Brooks, NDG Special Contributor

A typical young, black male in football and basketball glides down a gilded pathway by the time they are seniors in high school in both of those sports. My brother Chet, a blue chip, Parade All American as a senior, had bags of letters from every major university in the nation when he was a senior at Carter High School. You know this story well as you see it play out every year across high schools in Texas: Notre Dame, USC, UCLA, Florida State, Oklahoma, Michigan, Alabama, Miami, Ohio State, Texas, LSU, Nebraska; they all came calling on gifted young black males to help transform or maintain their programs.

Indeed, this is the accustomed stance for young black men: the decision where to lay their roots at many of the nation’s finest colleges and universities. In Chet’s case, all these same schools beckoned him to sign with their program, not only because of his football skills, but his academics were through the roof as well. Those programs that were recruiting Chet obviously know talent, as Chet, years later landed in the Texas Black Sports Hall of Fame, the Texas A&M Hall of Fame, and earning two Super Bowl rings from his time as an All-Madden Safety with the San Francisco 49ers.

Well, I see Hardy as a modern-day version of Chet, but with a major variant in play. He resides in a sport that appears conflicted at all levels (youth, college and pro) about how much leeway to give a young, black baseball player.

In Hardy’s case, he may have arrived before his time in a collegiate sense. It doesn’t appear that deserving kids like Hardy – for all of their merits on and off the field – will be able to entice the “gatekeepers” at college baseball’s highest levels to “pull a Bear Bryant,” where Bryant, in the early 70s, decided all-white football squads were passé. Bryant helped lead Alabama out of the dark ages, taking the entire college landscape (SMU, USC are among the enlightened programs that had previously diversified their squads) with him as his move to black ballplayers finally ushered in widespread acceptance on most campuses and thus allowed blacks to finally compete with the nation’s best and on the best teams in the nation.

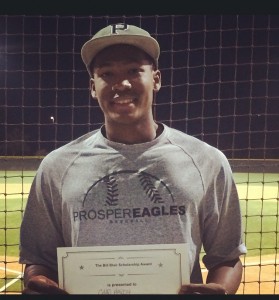

Though Hardy has the talent to allow him to play for virtually any school in the nation, he has fruitlessly performed in front of schools like Louisiana Tech University, the University of Arkansas-Little Rock and Stephen F. Austin. For some reason, those schools and others aren’t biting.

Let’s recap, MLB is impressed to a degree, but not any of the schools mentioned above.

Of course to even attend college while playing baseball is an honor, no matter the level. Here’s why: according to NCAA statistics, of the 137,000 high school seniors who play baseball each year, 6.8 percent of those players will make it to the NCAA level. It is estimated that less than 5 percent (compared with 42 percent and 32 percent for both NCAA basketball and football) of NCAA baseball players are black, with the majority of those players residing in the places like the historically black SWAC, MEAC, and CIAA conferences among others. A running joke among black baseball coaches is that even those conferences are no safe haven for talented black baseball players these days, with

programs like Lincoln University and other predominantly black colleges evidently unable to find black players.

For some odd reason the juxtaposition of Major League Baseball’s positive acknowledgment of Chad’s abilities versus the lukewarm reception on behalf of colleges and universities personifies the sport for a typical black player these days.

Why?

Among other reasons, take your pick: Gatekeepers (definition: those in control of who shows up on the baseball field for each college or university) who want to ensure that blacks never dominate baseball in the way that football and basketball is; the fact that baseball is considered a partial scholarship sport at the college level, and where players have to foot as much as 75% of their tuition bill (unlike football and basketball which are 100% funded scholarships); the cost of travel ball to get on the “map” of college recruiters; college coaches afraid the black player from a single parent home will want to eschew their scholarship in favor of getting drafted to help their families financially and thus not “waste” precious time and resources in pursuit of a player who will most likely spurn their offer.

There is also the thought that many white baseball coaches either don’t want to or don’t know how to interact with the black player (think back to the Oklahoma incident in 2005 where long time Oklahoma coach Larry Cochell let out this little gem: “There are honkies and white people and there are niggers and black people, Dunigan (his lone black player at the time) is a good black kid.”) and will have to spend time ingratiating players into the culture of their all or largely white rosters. Cochell’s involuntary resignation soon followed. Perhaps in hindsight, Cochell may have wished he had not ever allowed Dunigan to play for him; then of course Cochell’s stellar career would have continued uninterrupted. That interaction thing seemed to get in the way in the end. Or perhaps Cochell’s choice of verbiage in front of ESPN announcers was just a knucklehead move that should have rightly got him fired. But that 10-year old incident has not quite died in the minds of parents of black players who feel the cultural issue is one that some baseball coaches just don’t want to deal with.

Interpretation: Black ballplayers go ahead and have a field day in college basketball and college football but we don’t roll like that in college baseball.

One thing for sure, the Chad Hardy’s of the world deserve better. Paris Junior College is good baseball program and may indeed be a great landing spot for the Hardy’s of the world, but are you kidding me?