Source: newsamericamedia

Editor’s Note: The Western United States baked in the heat last week, with record-setting temperatures seen in Las Vegas, NV and Death Valley, Calif, as well as in California’s Central Valley, Oregon, Washington, and Utah, among other states. In some places, the deadly heat combined with extreme drought conditions and dry thunderstorms to fuel wildfires, including the massive Yarnell Hill fire in Ariz. A new study published this week in Environmental Health Perspectives makes a link between heat waves and public health. NAM’s Ngoc Nguyen spoke with study co-author Dr. Rachel Morello-Frosch, a professor in the School of Public Health at UC Berkeley about who is most vulnerable to the phenomenon known as the “heat island effect.”

New America Media: What is heat island effect?

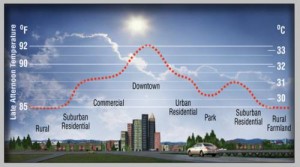

Dr. Rachel Morello-Frosch: Places that have a lot of impervious surface, like a lot of asphalt, cement and very little tree canopy – all these conditions can increase the mean temperature in your neighborhood by quite a bit and can cause a temperature difference of up to 10-15 degrees. It’s particularly noticeable in a heat wave.

NAM: What did you try to find out in the study?

RMF: What this study did was look at over 300 metropolitan areas across the United States and Puerto Rico to look at potential racial disparities at the neighborhood level for heat island risk.

We looked at disparities in tree cover. Trees provide shade and mediate the effects of heat waves in cities. If you live in a place with a lot of asphalt, which absorbs the sun — say, the streets of New York City, where there are no trees on a super hot day — you know what it feels like. Then, when you walk on a shady street you notice the [temperature] difference.

[Finally], we mapped the distribution of heat island risk across racial and ethnic groups and also by degree of racial residential segregation – meaning we wanted to see if there were differences in heat island risk depending on if they lived in highly segregated cities versus less segregated cities.

NAM: What did you find?

RMF: After accounting for the fact that there are definite differences across cities in the ecology of trees and differences in … rainfall, we found that African-Americans, Asian and Latinos are much more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to live in neighborhoods with a lot of heat island risks. Blacks across the country were 50 percent more likely than whites to live in high heat island risk neighborhoods, Asians were 30 percent more likely and Latinos were 20 percent more likely…

We also saw within each racial [and] ethnic group that health island risk increased with increasing levels of segregation. In other words, in cities characterized by high levels of segregation, people tended to have higher levels of health island risk compared to their less segregated counterparts.

NAM: What accounts for greater health island risk in hyper-segregated cities?

RMF: What we are seeing in the physical environment — the planting of trees and infrastructure that tries to decrease heat island risk in cities — these kind of investments, you tend to see less of in places with high levels of racial inequality. The physical environment in cities is a reflection of the social environment, and it tends to disadvantage people of color particularly.

It’s possible in cities with higher levels of segregation, there is less investment to protect people from health island risk, such as tree-planting campaigns, greening of space and neighborhood, reduction in impervious surfaces that really absorb heat, whiter roofs, those kinds of things, certain levels of public investment.

NAM: The Census accounts for racial segregation in cities – how do they define it and how many people are living in hyper-segregated places?

RMF: Thirty-five percent of the U.S. population is living in the most segregated cities in the country. In our study, out of 300 metropolitan areas, we found 24 metro areas considered to be hyper-segregated. The measure is a number between 0-100 percent and describes what proportion of the residents in the metro areas would have to move to achieve an even distribution of racial and ethnic groups. The term highly segregated means that 50 percent or more would have to move.

NAM: What are the health impacts of heat waves?

RMF: Dehydration, and increased rates of hospitalization for dehydration and heat exhaustion. People already suffering form chronic illnesses like hypertension or diabetes are more vulnerable to the adverse health effects of extreme heat events; people can also die from being exposed to heat, especially if they don’t have air conditioning. You have situations in which some people have air conditioning in their homes, but they still end up in hospitals. They haven’t turned it on, because they can’t afford it. People whose homes are super hot are encouraged to go to cooling centers … they just need to get to a safer place. But some don’t have access to a car or public transit, so their ability to protect themselves is minimized.

NAM: What was surprising in the study findings?

RMF: In metropolitan areas with greater levels of racial segregation, everyone — whites included – were more likely to live in heat-prone areas … what this shows is that, in some ways segregation adversely affects everyone. This form of social inequality affects everyone. Segregated places have much higher health island risk compared to less segregated places.

NAM: What implications does the study have for policy?

RMF: I think this research shows us that local land cover can have a dramatic effect on the heat experiences of … urban residents. This research suggests efforts should be attuned to racial disparities [and] directing heat-mitigating strategies to the most vulnerable residents in these cities.

The study suggests that when you are in a city that is more racially segregated, [where] race or ethnicity dominates how people live with each other … there is less concern about the common good.

In terms of climate change, where collective investment in adaption is precisely what is needed to protect people who live in urban areas … we need to take into account racial inequality, and plan adaptation strategies to protect the most vulnerable.