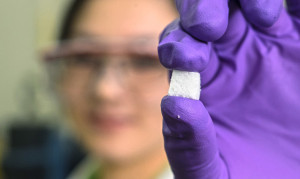

Scientists have created a new composite material that is half liquid, but it doesn’t leak when cracked.

And it can quickly heal, over and over. Like a sponge, it returns to its original form after compression.

The material called SAC (for self-adaptive composite) consists of what amounts to sticky, micron-scale rubber balls that form a solid matrix. Researchers at Rice University made SAC by mixing two polymers and a solvent that evaporates when heated, leaving a porous mass of gooey spheres.

Other “self-healing” materials encapsulate liquid in solid shells that leak their healing contents when cracked.

“Those are very cool, but we wanted to introduce more flexibility,” says Pei Dong, a postdoctoral researcher who co-led the study with Rice graduate student Alin Cristian Chipara. “We wanted a biomimetic material that could change itself, or its inner structure, to adapt to external stimulation and thought introducing more liquid would be a way. But we wanted the liquid to be stable instead of flowing everywhere.”

They think the material could be a useful biocompatible material for tissue engineering or a lightweight, defect-tolerant structural component.

TOUGH LITTLE SPHERES

In SAC, tiny spheres of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) encapsulate much of the liquid. The viscous polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) further coats the entire surface. The spheres are extremely resilient, Lou says, as their thin shells deform easily.

Their liquid contents enhance their viscoelasticity, a measure of their ability to absorb the strain and return to their original state, while the coatings keep the spheres together. The spheres also have the freedom to slide past each other when compressed, but remain attached.

“The sample doesn’t give you the impression that it contains any liquid,” says material scientist Jun Lou, who co-led the study. “That’s very different from a gel.

“This is not really squishy; it’s more like a sugar cube that you can compress quite a lot. The nice thing is that it recovers.”

HALF LIQUID, HALF SOLID

Making SAC is simple, says study co-leader Pulickel Ajayan, and the process can be tuned—a little more liquid or a little more solid—to regulate the product’s mechanical behavior.

“Gels have lots of liquid encapsulated in solids, but they’re too much on the very soft side,” he says. “We wanted something that was mechanically robust as well. What we ended up with is probably an extreme gel in which the liquid phase is only 50 percent or so.”

In tests, the scientists found a maximum of 683 percent increase in the material’s storage modulus—a size-independent parameter used to characterize self-stiffening behavior. This is much larger than that reported for solid composites and other materials, they said.

Dong says sample sizes of the putty-like material are limited only by the container they’re made in. “Right now, we’re making it in a 150-milliliter beaker, but it can be scaled up. We have a design for that.”

They describe the results in the journal ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces.

Additional researchers from Rice, the University of Texas-Pan American, and the State University of Campinas, Brazil, collaborated on the project, which received support from Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the Department of Defense.

Source: Rice University and Futurity.org