By Allen R. Gray

The line of demarcation that lies between those who get and those who get not was once defined as by the Trinity River. Now, the line has shifted to anything south of Illinois Avenue thanks to gentrification. The avenue is the political difference between the haves and have nots…which is to say the difference between struggling Blacks and Latinos and more affluent whites.

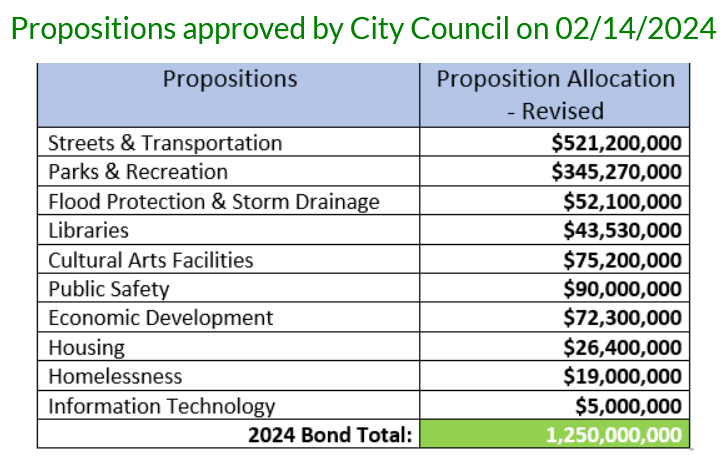

The new $1.25 billion package that was recently approved by the Dallas City Council is an issue that deserves to be looked into deeply and what the process entails before stepping into the ballot box this coming May, especially if your domicile lies south of Illinois Avenue.

From its inception to its dollars spent, bond programs are a legislative process that is in no way a casual undertaking.

A bond program is an ensuing debt that is issued by voters; and that debt service must be paid back by the City over time and funded by taxpayer dollars. Bonds funding is an instrument accessible to Texas counties, and even a state bond is possible.

A bond is essentially an exceedingly expensive Christmas wishlist that is drafted by city officials.

The life of bonds are not decided by a single vote that will determine the passing of the entire program. Instead, a bond program is a series of desired propositions aimed at funding a city’s improvement needs. The Texas Legislature recently passed a law requiring that all local government propositions be lettered, and state propositions be numbered. The 2024 bond program has a total of 10 individual propositions, which voters will be asked to consider each independently during the May 2024 election. The final funding of a bond program is paid by we the taxpayers.

There are two components to the City’s tax rate: the general fund supports the Maintenance and Operations tax rate; and bonds repayments are paid by the debt service rate. During the analysis of the 2017 bond program, for every $100 valuation the debt service rae was $22.24.

Well over a year ago, Dallas Mayor Eric L. Johnson announced his appointments for the Community Bond Task Force (CBTF) subcommittees. Each CBTF subcommittee is comprised of 15 members charged with determining the City’s needs for capital improvement projects. Each subcommittee is overseen by one of five appointed chairs.

The five subcommittee chairs appointed by Mayor Johnson include:

• Lind Koop, Streets Subcommittee

• Jennifer Staubach Gates, Critical Facilities Subcommittee

• Garrett Boone, Parks & Trails Subcommittee

• Anita Childress, Flood Protection & Storm Drainage Subcommittee

• Tony Shidid, Economic Development & Housing Subcommittee

Bond in and of itself is not a four letter word. There is good to be had when the vehicle in question is operated in the manner in which it was sold.

But before looking ahead to what this recent bond proposal might offer it will serve us well to view how a bond packages of the recent past served the city and its residents.

The 2017 bond program also had 10 individual propositions that were lettered A-J; and had a bond total of $1.050 billion. Voters unanimously passed all 10 propositions. The biggest vote-geter was Porposition A: Streets and Transportation with 78.71% of the votes. The least desired was Proposition I: Economic Development, but it still carried 60.97% of the vote.

The flagship proposal of the 2017 bond package was Poposition A: Streets and Transportation. The first question that begged to be answered was: Were the preponderance of those street repairs done above or below Illinois Avenue?

It is a wise precaution is to view a map of exactly where the street work was done—to determine if the repairs were done disproportionately either above or below that Illinois Avenue line of demarcation.

So the links that leads one to a map of those street repairs were followed…

There was no map available for viewing.

The next move is to find some map (any map) that was available.

The available map was the one that depicted the Bikeway System: Overall Network. That depiction inspired a question posed to some residents residing to the south of Illinois Avenue.

That led to the next essential question: Do you need or even want a bike path?

An informal survey was conducted. The respondents were a small sample size of Black and Hispanic men, who retorted with a predictable and nearly uninamous “Hell naw!”

The map showed that a moderate number of bike paths were added below Illinois Avenue—but starting from that dividing line going north, the number of bike paths coursed out and through like varicose veins.

The most important question that begged to be answered was: Into whose bag did the 2017 bond dollars land?

A report of executed contracts provided by the Department of Public Works showed that for pavement maintenance and road resurfacing fees for a 36-month period the sum of $288,906,900 was paid out. One company, Texas materials, Inc., put $53,686,607 into its bank account. The remaining $208,551,849 went straight into the bag of heritage materials, LLC.

Despite the critiques of past bond packages, the 2024 Bond Program will more than likely pass (affected no doubt by low voter turnout), but it did not pass unanimously with the Dallas City Council vote.

Every City Council member voted infavor of the 2024 Bond Program…save one: Council Mamber Adam Bazaldua, who wanted them to allocate funds to repair the neglected structure known as City Hall. Bazaldua offered up his own set of bond allocations for the May ballot. The other coucil members cut him off at the knees.

The biggest battle centered around the 2024 Bond Program is going to be how do minority companies and business owners have themselves included in the procurement process.