By Enrique Rivero, UCLA

It was a typical misunderstanding that could have led to disastrous consequences. The man had run out of medication to control his hypertension. But he couldn’t afford to get it refilled, or so he thought.

So instead of picking up a simple, generic medication at Wal-Mart or Target for $4, the man decided to go without it and unknowingly put himself at risk for a stroke. All because he didn’t realize he could obtain the medication cheaply.

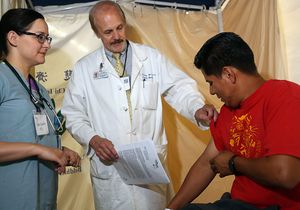

Fortunately, he was one of hundreds who were treated by UCLA health care workers volunteering at the Care Harbor’s annual health clinic held Sept. 11-14 at the Los Angeles Sports Arena. His story is typical of many who come to this free clinic for the poor and underserved, said Dr. Patrick Dowling, chief of the UCLA Department of Family Medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine.

About 30 percent of those who saw a UCLA health care worker at the clinic had prescriptions that went unfilled.

The man’s predicament, which was remedied by a simple referral to a local pharmacy, also explains why UCLA’s participation in the annual free clinic is so important and gratifying for the volunteers, among them, nurses; cardiologists; ear, nose and throat specialists; family medicine physicians and ophthalmologists from the Stein Eye Institute. Their ranks also included family medicine sports medicine doctors, International Medical Graduate (IMG) program participants, and medical residents and students from UCLA.

This year, an estimated 4,000 people attended the clinic, up from around 3,000 last year. Mostly poor and uninsured, they came for dental work, eye care, general internal health care and other services.

The volunteers also gain something valuable, said Dr. Brenda Green, a third-year family medicine resident at UCLA. She is a graduate of the IMG program, which assists bilingual, bicultural immigrant medical school graduates from Latin America who reside in the U.S. legally, with earning a California medical license and obtaining a residency in family medicine.

Working at the Care Harbor clinic gave her the opportunity to work with the underserved populations that she will treat once she’s finished her residency. To be in the IMG program, physicians must commit to practicing in one of the state’s more than 500 underserved communities for two to three years after completing their three-year family medicine residency.

“I love working with the Hispanic population since I speak Spanish and I can communicate with them,” said Green, who volunteered at the clinic last year as well.

Most of the people she saw suffered from chronic pain or women’s health problems; diabetes was particularly common, she said. The clinic offers referrals to patients who are diagnosed with other untreated health conditions, some of them serious.

“There’s a strong Hispanic population, and diabetes is prevalent among them,” said Green. “A lot of it is uncontrolled.”

A medical student in the IMG program, Daniel Handayan found that volunteering at the clinic gave him the opportunity to use some of the skills he had learned at the Universidad Autonomo de Guadalajara, where medical students are exposed to clinical care earlier than in the U.S.

“I wanted to give back to Los Angeles,” said Handayan, who was born in Pasadena. “This is a great opportunity to use the skills I learned in Mexico.” He was one of nine IMG students who participated during the four-day clinic.

“They’re valuable because of the language and culture,” Dowling said.