After years of establishing and strengthening sex offender registries, some states are rethinking policies allowing juveniles to be placed on them.

In states such as Oregon and Delaware, lawmakers have given judges more power to review who goes on the registry. In Pennsylvania, courts have ended lifetime registration for juveniles.

Driving the changes are concerns that putting juveniles’ names and photos on a registry—even one only available to law enforcement, as in some states—stigmatizes them in their schools and neighborhoods and makes them targets of police, sometimes for inappropriate behavior rather than aggressive crimes. Also of concern are laws that add youth sex offenders to adult registries once they turn 18 or 21, even though they were tried as juveniles, not adults.

Human Rights Watch in a 2013 report pointed to the case of a 10-year-old Michigan girl who served time after she and her younger brothers flashed one another in 1991. She was placed on the state’s adult registry when she turned 18. The report also cited a Texas juvenile court that convicted a 10-year-old of indecency with a child for touching a younger cousin—a crime resulting in lifetime registration.

Registries Vary

State laws requiring juveniles to register as sex offenders came into wide practice after Congress passed laws such as the 1996 Megan’s Law and the 2006 Adam Walsh Act, which were named in memory of children murdered by sex offenders. They were designed to better track sex offenders and make information easily accessible to law enforcement and the public. They sought more community notification and greater consistency among state registries.

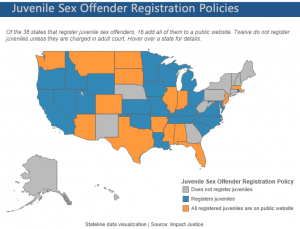

Thirty-eight states now add juveniles to sex offender registries. The remaining 12 states only add the names of youths convicted in adult courts.

States with juvenile registries vary greatly in what they require. Sixteen states publish juvenile offenders’ names, addresses and photos on a website. In some states, youths may petition to have their name removed from a registry, although it can take more than a decade before they can begin the process. Some states add names to a registry for a set amount of time, while others keep offenders on the list until they die. As their photos are updated through the years, the offenders begin to look less like children and more like pedophiles.

Supporters of juvenile registries say they’re important for public safety, and serve an important purpose for families and victims. Opponents say the penalties are too harsh for children who have been intentionally kept out of adult court.

Nicole Pittman, director of the Center on Youth Registration Reform at Impact Justice, said registries are contrary to the concept of juvenile courts, which are based on the premise that children are more capable of change and should be shielded from the harsher consequences of adult court.

Research shows a child convicted of a sex crime, or an “adjudicated delinquent” in juvenile court, is not likely to commit another sex offense.

Although the recidivism rate for adult offenders is low, generally around 10 percent, youth sex-offender recidivism is usually less than 5 percent, said Elizabeth Letourneau, a professor with Johns Hopkins University and an expert on juvenile sex offenders.

She said registry policies don’t make sense because they’re applied across the board to people who are very unlikely to commit another offense. “A lot of them don’t know what they’re doing is wrong, but they learn that very quickly, though, once they’re going through the legal process,” Letourneau said.

She said the registries can have a scarlet letter effect on children. They tend to be more depressed and anxious than their peers, and have less stability because they are shuffled from school to school and family to family, she said.

Another concern: Even when someone is removed from a registry, the information can remain on nongovernmental sites for years. Even those who aren’t placed on public registries still may have to notify nearby schools or have a postcard sent to addresses within so many miles of their house.

Pittman said people often don’t see why children who aren’t on public websites are affected, but things like mailers are a big deal.

“When you think about a child’s life, that 3-mile radius is their life,” she said, which includes many of their friends, neighbors and classmates.

Pittman said that when people have access to an offender’s address, it is not uncommon for people to vandalize property or otherwise target the house. But because many offenses are carried out within the home, often between siblings or cousins, vigilantes aren’t just terrorizing the offender but often the victim, as well.

Registered children also are more likely to be targeted by police. Letourneau found registered children were more likely to get charged with new nonsexual offenses than juvenile offenders who were not required to register. Even with the increase in arrests, registered children were no more likely to be convicted of these new crimes than their nonregistered counterparts.

Advocates worry that the effects make it harder for children to be rehabilitated, something juvenile prosecutors may be aware of. Letourneau’s review of data from South Carolina found that prosecutors would plead children out on nonsexual charges, say from sexual assault to physical assault, after penalties increased. She said the number of plea deals skyrocketed after two federal laws were passed, one in 1994 that required registering people who commit sex crimes against children and the other in 1996 that required them to be added to a sex offender website.

Although many advocates say states shouldn’t have juvenile registries, they point to Oklahoma as having a better system than most.

Oklahoma’s juvenile registry is accessible only by law enforcement, and children are only considered for registration if a prosecutor determines that they might commit another offense and files an application to have them added to the registry when they are released from custody. Once released from treatment, the juvenile meets with two mental health professionals who report back to the court to help the judge decide whether to add the child to the registry. In the first 10 years of the registry, only 10 juveniles were added to it.

Slow Changes

Changes to the laws have been slow. Oregon this year passed a law giving juvenile judges more discretion over whether youths should be registered. Previously, all children convicted of a felony sex offense were automatically registered for life. Now, once youths complete their sentence, another hearing is set so the judge can review how they did in treatment and weigh their likelihood to reoffend before choosing whether or not they need to be registered.

“Having to register as a sex offender is tough. If you deserve it, I don’t feel sorry for you. But if you’re a juvenile, then you have to spend the rest of your life not being able to coach your children, go to their schools or find a place to live,” said state Rep. Jeff Barker, an Oregon Democrat and the chairman of the House Judiciary Committee.

He said he didn’t think it was fair to make all juveniles register, but he didn’t think there should be no registration either.

Mark McKechnie, director of Youth, Rights & Justice, which pushed for changes to Oregon’s law, said it can be tough to get support for bills that drastically change the system.

“The policy world is slow to react to that because of the nature of the subject. It’s an easy target in elections,” he said.

In Missouri, legislators passed a bill in 2013 that would have given juvenile sex offenders the right to petition to be removed from the state’s lifetime registry. But Democratic Gov. Jay Nixon vetoed it, saying there were dangerous people among the 870 that could petition. He said the bill would “undermine public safety and victims’ rights.”

The state’s policy came before the state Supreme Court this year when a 14-year-old St. Louis boy convicted of attempted rape in a juvenile court challenged being placed on Missouri’s public adult registry when he turns 21. But the state Supreme Court dismissed the case, saying it was “not ripe for review at this time.”

In Delaware, the state’s public defenders lobbied for five years to loosen restrictions because the state had children as young as 9 years old on their registry. Lisa Minutola, chief of legal services for the state office that oversees public defenders, said that as a result of 2013 legislation, judges now can relieve children under 14 of the requirement to register. That also is an option for children age 14 to 17 who commit less serious crimes.

Ohio was the first state to become substantially compliant with the Adam Walsh Act, which requires more stringent registration practices from states. A number of challenges have chipped away at the state’s registry though, and children no longer are placed on a public website, nor are they subject to automatic lifetime-registration.

In Pennsylvania, the state didn’t try to become compliant with the Adam Walsh Act until 2011, when it faced losing some federal dollars. But the law’s lifetime-registration requirement was overturned by the state’s Supreme Court in 2014.