By Jessica Wolf, UCLA

While the #OscarsSoWhite controversy raged over the dearth of people of color nominated for Academy Awards this past year, a group of digital humanities students at UCLA channeled their frustration into meticulously reconstructing the little-known history of silent films made for and by African Americans in the early 20th century.

What they found, and sought to highlight, is that African-American artists are deeply entwined in the history of filmmaking, and can be traced back to the medium’s beginnings.

The result of their efforts is “Early African American Film: Reconstructing the History of Silent Race Films, 1909–1930,” an informational website and searchable database that tracks the African-American actors, crewmembers, writers, producers and other artists who were making films during the silent era.

“Even though so few films remain, they offer this alternative vision of African-American life in the first half of the twentieth century that’s so much more rich and complex than many things in mainstream film,” said Miriam Posner, digital humanities core faculty member and program coordinator. “You have these incredible actors and personalities like Lawrence Chenault, Evelyn Preer and Noble Johnson. You can just get lost imagining what it must have been like to have been so committed to your craft at a time when your work was so terribly undervalued.”

Students were immediately hooked on the topic, Posner said and many of those who worked on the project got their first experience with UCLA special collections and primary-source research through it.

“One thing I love about UCLA students is that they have so much passion about understanding and attempting to redress historical wrongs,” Posner said. “They hadn’t known about this filmmaking culture, and they couldn’t believe no one had ever mentioned it to them.”

Students worked closely with UCLA Library Special Collections, combing through old journals, production notes, posters and flyers to reconstruct what was once a thriving and collaborative network of African-American writers, directors, actors and producers who were making what were known as “race films.”

“We were venturing into pretty unknown territory and I really wanted to be a part of telling the stories of this generation of African-American people and their contributions” said Shayna Norman, who graduated last spring. “The fact that the #OscarsSoWhite controversy blew up at the same time we worked on it, made this project feel even more relevant and important.”

Relying partially on the work of historians who have unearthed documentation of these forgotten filmmakers, the UCLA student team set its parameters to include films from 1909 to 1930 that featured African-American cast members, were produced by an independent production company and discussed or advertised as a race film in the African-American press.

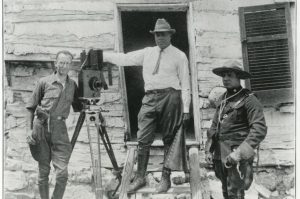

While the community was vibrant, it struggled to gain mainstream traction. In the silent-film era, productions that fit “race films” description, like those produced by the Hampton and Tuskegee Institutes, “A Trip to Tuskegee” (1909), “John Henry at Hampton” (1913) and “A Day at Tuskegee” (1913) could be shown only in certain theaters, or often African-American churches, and were played to segregated audiences. Most of these films, therefore, received scant mainstream media attention. The actual film reels were not preserved in any systematic way or protected in hermetically sealed vaults, which has led to physical degradation.

Few films survive, though Posner was partially inspired to start the project thanks to the recent release of a compilation of films from Kino Lorber International called “Pioneers of African-American Cinema.”

The scarcity drove the students.

“I love archives and am really interested in the ethics of the archive and archiving in general,” said Hanna Elyse Girma, who was part of project before graduating last year. “Reconstructing the most comprehensive database we could was really exciting to me, even though we had a lot of challenges.”

Coming up empty on internet searches caught students particularly off guard, Norman said.

“We’re not used to that kind of obscurity, but so much of the data has been lost or damaged, is not in any history textbooks in our educational system, and is not easily searchable,” she said.

A centering figure in the student’s archival spelunking was Oscar Micheaux, author, filmmaker and founder of the Micheaux Film Corporation, one of the most prominent producers of the era’s race films and who kept copious notes and records of the actors and crewmembers he worked with, providing much needed fodder for the database. Micheaux’s “Within Our Gates” (1919) is one of the few examples of a race film that garnered some attention — and an audience — from the white press.

The project exists as a perusable database on the code-sharing site called Github, which others may use, build upon and correct. The site maintains a trail of attribution to the UCLA project.

“Not everyone knows how to work with data like ours, so we also spent a lot of time building tutorials that show people exactly how to create their own network graphs, maps, and other kinds of analysis using our data,” Posner said.

Capstone activities like this are extremely important in the digital humanities field, because students have the best, most-meaningful experiences while apprenticing on an active project, she said.

Working on a project like has made lasting impact on the students.

“I’m a media junkie and by being involved in digital humanities projects like this one, I can see how such digital research methods and skills are relevant and needed in this growing age of mass consumer media,” Norman said.