By Terri Schlichenmeyer

You‘d need that pin to get in.

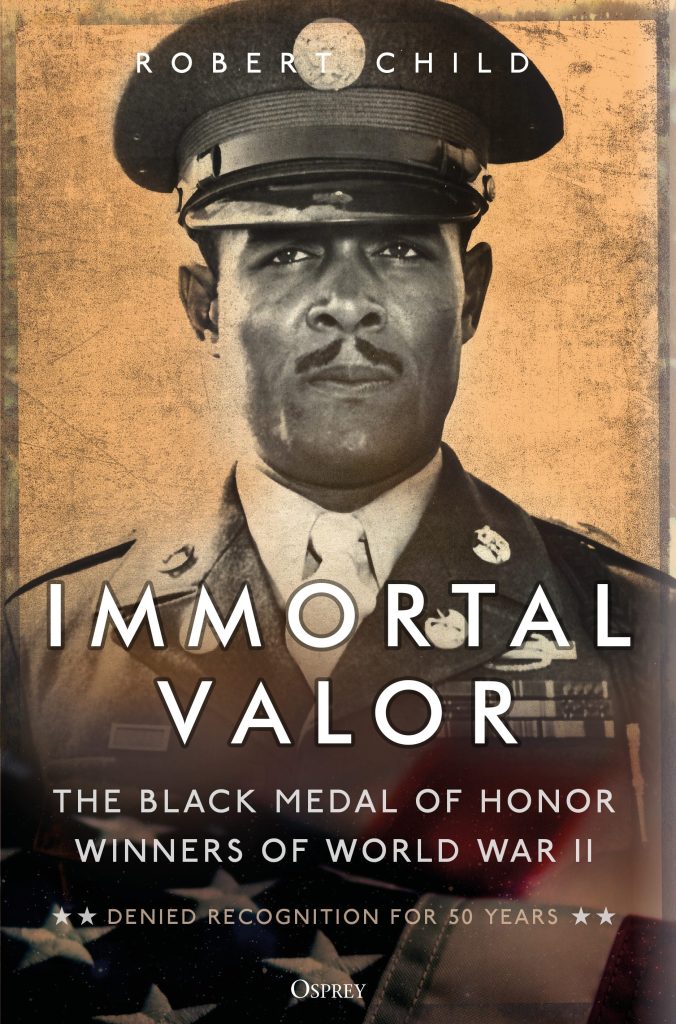

Put it on your chest and you’d get access to an exclusive club. The pin tells the world what you did, that you were elite, that you acted with honor. If you earned the pin, you’d wear it with pride. In “Immortal Valor” by Robert Child, it’s a beribboned thing that you‘d definitely deserved.

Almost since the birth of this country, soldiers who have exhibited bravery above and beyond their normal duties have been given medals for military merit. Says Child, almost 3,500 Medals of Honor have been awarded so far in the history of America; “Less than 3 percent… have been awarded to… African Americans…” Of the 500 Medals of Honor awarded for service during World War II, just seven of them went to Black soldiers.

That may not be a surprise. Racism was an everyday occurrence then and Black soldiers “knew only segregation” which “meant inequality.” Even so, the men in this book didn’t let racism stop them from serving their country. It didn’t stop them from exceptional acts.

That may not be a surprise. Racism was an everyday occurrence then and Black soldiers “knew only segregation” which “meant inequality.” Even so, the men in this book didn’t let racism stop them from serving their country. It didn’t stop them from exceptional acts.

Charles Thomas was working at Ford in Dearborn, Michigan, when he was drafted into the Army. In the midst of battle in Climbach, France, Thomas was injured but continued to lead his men.

If Vernon Baker hadn’t seen much racism at home in Wyoming, he surely saw it after he enlisted in the Army. It was never as blatant, though, as it was when a white officer was given credit “for the actions [which Baker] performed…”

Willy James was killed trying to reach “his fatally-wounded platoon leader.” Edward Allen Carter Jr. was fifteen years old and living in Shanghai with his missionary family when he volunteered to fight with the Chinese; four years later, he visited the American embassy and asked to be assigned to Abyssinia with the American troops.

George Watson lost his life attempting to save one. Ruben Rivers went into the Army with his younger brother. John Fox left a prestigious college to attend one with an ROTC program, so strong was his desire to serve…

So what makes these men unique? Author Robert Child explains the rest of the story: in 1993, a study showed that these men didn’t get the honors for which they were recommended. It took another four years before they finally received their medals, more than five decades after wars’ end. Child tells readers how this happened; he also says that other men are still waiting.

That all makes “Immortal Valor” part irritation, part history. The former lies waiting, wrapped in small biographies of those men, Jim Crow tales, and stories of valor so long unrecognized. The latter could be a bit of a challenge for civilians: along with tales of American society, it’s a lot of battles-and-dates information that, even so, pulses with adrenaline, blood, screams, and jaw-dropping bravery.

Go into “Immortal Valor” knowing this and you’ll burst with outrage and pride at nearly every word. Especially for veterans and their families, this is a book to pin down.