By Terri Schlichenmeyer

What was your favorite possession when you were a child?

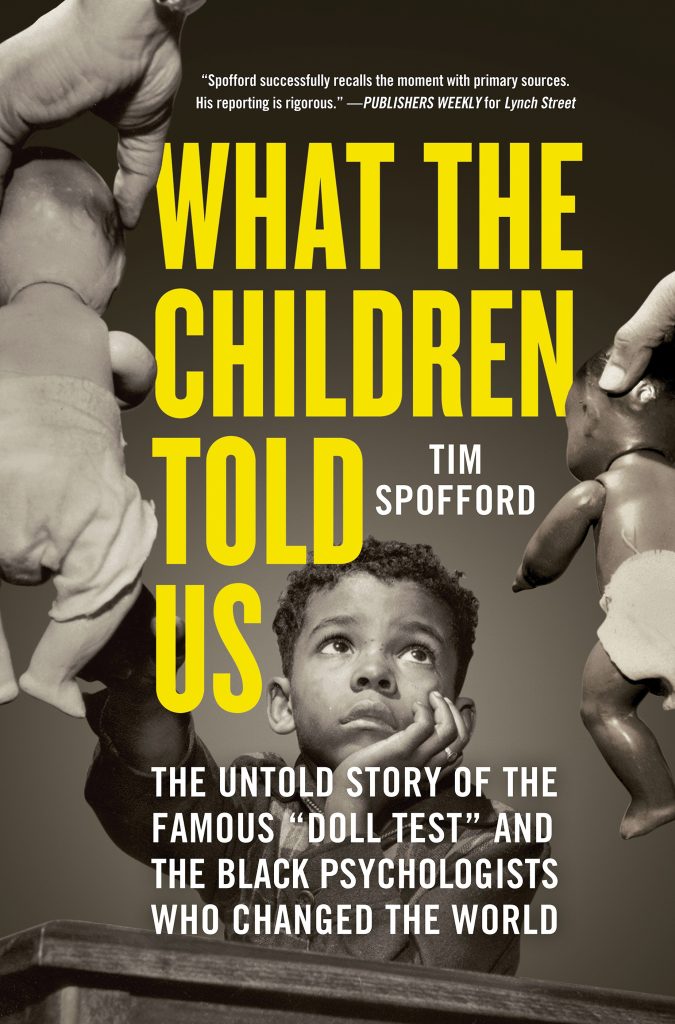

Of course, you remember it, the weight of it in your hands, the way it fit your fingers, the envy of your peers, the pretending fun of it, and the security of knowing it would be waiting for you after school. Toys are essential in childhood, important in some adulthoods, and in the new book “What the Children Told Us” by Tim Spofford, they’re key in understanding racism and inequality.

Kenneth and Mamie Clark had both grown up with the benefits that Black middle-class life bestowed on its members in the 1930s and ‘40s. Still, they were both grad students when they eloped and after their marriage, his research and her job kept them in different cities.

Her family didn’t approve of him; Kenneth was driven, Mamie was focused, and in those Jim Crow years, they both keenly understood the effects that racism has on the human psyche. Rather than let it deter them, though, they complemented and supported one another and used that inequality to form their careers.

Her family didn’t approve of him; Kenneth was driven, Mamie was focused, and in those Jim Crow years, they both keenly understood the effects that racism has on the human psyche. Rather than let it deter them, though, they complemented and supported one another and used that inequality to form their careers.

In 1939, Mamie began studying the effects of racism on young children, determining that self-awareness of race was set by age four, and publishing three articles on findings that gained attention from established psychologists. The following year, Kenneth, who’d become quite passionate about psychology himself, helped Mamie to set parameters for a project based on some of the data that “gnawed at” her. He also found the main ingredients for that project: four plastic baby dolls, identical except for their color.

Then the Clarks invited 253 Black children ages three to eight to a conference room in an integrated school in the North and in the segregated South, and they asked the children a question: which doll – the white one or the brown one – looked more like you?

Two-thirds of the Black children chose the white doll.

Questions. You’re going to have a bunch of them, once you’re finished with “What the Children Told Us.” The first one will be: why haven’t the Clarks taken their place next to other influential people in Black history?

The answer may be because most stories stop at the “doll test,” but not this one. Author Tim Spofford tells this decades-long story almost in three pieces: the Clarks’ backstory, which unspools pleasantly like an old-time movie; the “doll test” years in which the study was refined and processed; and the Clarks’ many years after the test which, quite surprisingly, were so important that they almost turn everything else into a footnote.

Indeed, readers who have, until now, been unfamiliar with the work of Mamie and Kenneth Clark will have their eyes opened. Spofford takes us well-past a nationally-shocking study to the streets, schools, the White House, and into history.

It’s a story you need to read, and it may leave you with more pesky questions. It may also inspire you because this is that kind of book. “What the Children Told Us” shows that heroes exist and activism is not child’s play.