By Terri Schlichenmeyer

At least you won’t have to move.

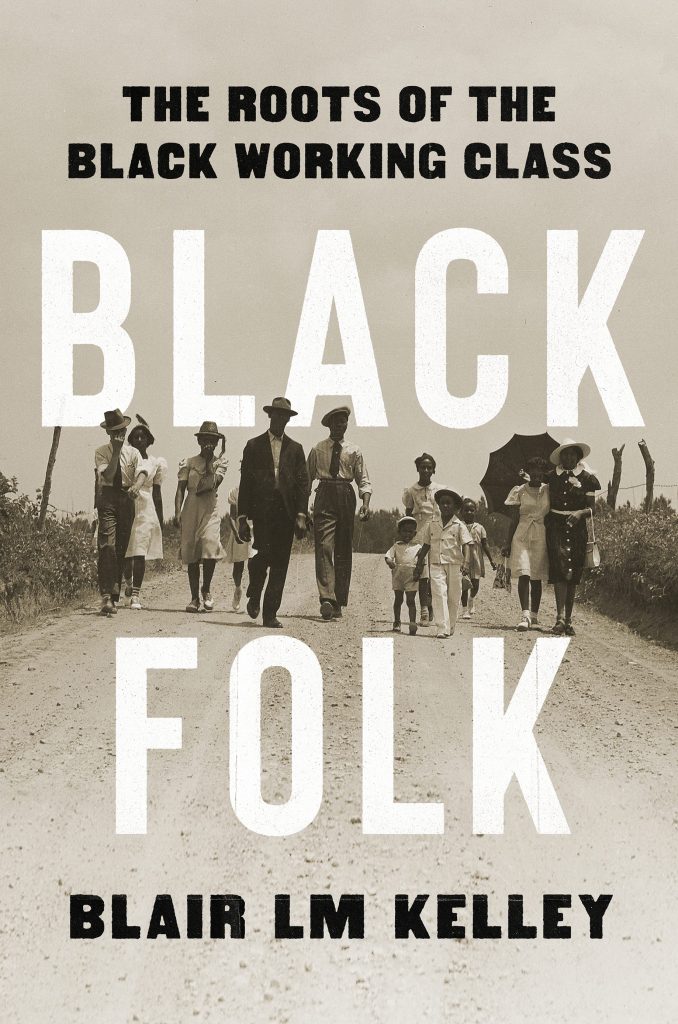

You keep telling yourself that, ever since the boss decided to downsize this year, workplace and all: a reduced staff and work-from-home options means a smaller office and big change, which is fine with you. In the new book “Black Folk” by Blair LM Kelley, your ancestors never had it this good.

In the years immediately following Emancipation, former slaves were shut out of nearly every job other than domestic and sharecropping and they “still faced circumstances almost as degrading as those of slavery.” Hoping for better lives, Black workers first headed from farm to big city, in the hope of landing good jobs.

“My work as a historian has always begun with the stories of my ancestors,” says Kelley and she opens this book with an angry man, his son, and the story of Henry, who was “born in bondage” and ultimately became a blacksmith. Kelley admits that she doesn’t know much about Henry’s earliest life but in adulthood, he became a voter and “he was part of a community” – something that Kelly “found time and again” had given “Black folks [a] sense of self.”

Like many Black women in the 1920s, Sarah Hill was a washerwoman hired to launder white folks’ clothes. It was an honorable job, one of the few available to Black women, but while it didn’t pay well, it paid enough for Sarah to put a little money aside. It allowed her some control over her own life then.

Callie House helped washerwomen organize. Cottrell Dellums belonged to an organization of Black Porters. As a young teenager, Minnie Savage was “near the front of a grand exodus north” when she snuck away from her parents home. To her great irritation, Minnie could only find domestic work in Philadelphia. And after moving north, Hartford Boykin landed a job but his past kept returning to him.

“From his mother, Hartford learned that Black freedom was precarious.”

Remember how totally dry your high school history books were? Yeah, this is nothing like those. “Black Folk” lets readers get to actually know people who lived a century ago or more. It’s like being carefully handed a living, breathing story to hold.

In using her own family tree as a launching point, author Blair LM Kelley lends detail to tales she’s heard all her life and knows well. This is no small thing: it assures readers that there’s authenticity inside every anecdote, that they’re not told with guesswork but with real first-hand knowledge. Alongside that, Kelley uses her experience as a historian to show how her ancestors represent most of the Black working class between roughly 1865 and 1940, and how their journeys were like so many others in the Great Migration.

On this, readers will be happy that both men and women stand tall here.

This is one of those books that’s meant to savor, to explore and enjoy. For historians and anyone who had a Great Migration ancestor, reading “Black Folk” is a good move.