By Terri Schlichenmeyer

You have all the tools you need.

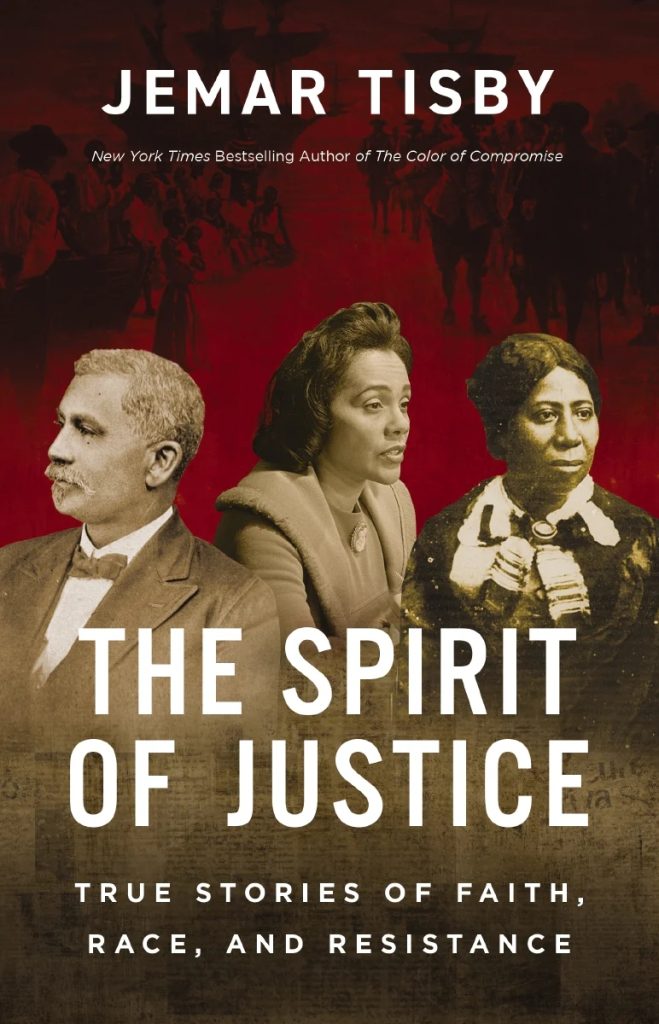

You have a level, so you’re always even-keeled. A hammer, to nail down your ideals. A saw to cut through nonsense and pliers to pull out the truth. You have almost everything you need for equality; now you need “The Spirit of Justice” by Jemar Tisby for the right blueprint.

In early December of 2017, Myrlie Evers-Williams “granted a private audience” with a group of journalists on the day that the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum opened. Jemar Tisby was in that group, and Evans-Williams’ remarks stunned him.

She said that “the spirit of justice raises up like a war horse… that stands with its back sunk in” until it “hears that… ‘bell of freedom.’ And all of a sudden, it becomes straight and the back becomes stiff. And you become determined all over again.”

This made Tisby think of all the people who have seen “the worst of humanity” and still kept going. He wondered how they did it.

Conversely Queen Nanny, a Maroon Black from Jamaica who practiced Obeah never let faith affect her fierceness for her people. Not coincidentally, she became “Jamaica’s only female national hero” in 1975.

John Punch was the first person to be legally considered “Black” in America. Richard M. Allen helped establish the AME Church and Jarena Lee was the first Black women to become an AME preacher. David Ingraham, a white missionary, sketched a slave ship in his journal before he became an abolitionist. Anna Murray Douglass, wife of Frederick Douglass, helped her husband “in every possible way…” Black people formed a militia during the Civil War, and started “black institutions” of higher learning when the war was over. Charles Hamilton Houston established the NAACP. And Prathia Hall inspired Martin Luther King, Jr. to speak his mind…

In his opening chapter, author Jemar Tisby says that he never intended to write about “perfect people who never did or said anything objectionable…”

He did, however, “focus on Black Christian resistance to anti-Black racism.” To that end, you’ll read about people who are familiar – Dr. King, Harriet Tubman, Phillis Wheatley, and others – but “The Spirit of Justice” also introduces you to a host of new heroes to admire.

Beware, though, that spotting them will keep you on your toes. Tisby rushes their stories through quickly, keeping the narrative from getting bogged down while also holding readers’ attention nicely. There’s a lot of strong, applicable-for-today information packed into this book, in fact, and it reads smoothly with an easy-to-follow timeline that’s easy on the brain.

Be prepared for tales that are wrenching, stories that’ll make you want to research further, and tales that are inspiring in both action and faith.

For adults, “The Spirit of Justice”is just right; for teens ages 15 and over, it’s a great book to have in the toolbox.