By Stacy M. Brown

NNPA Senior National

Correspondent

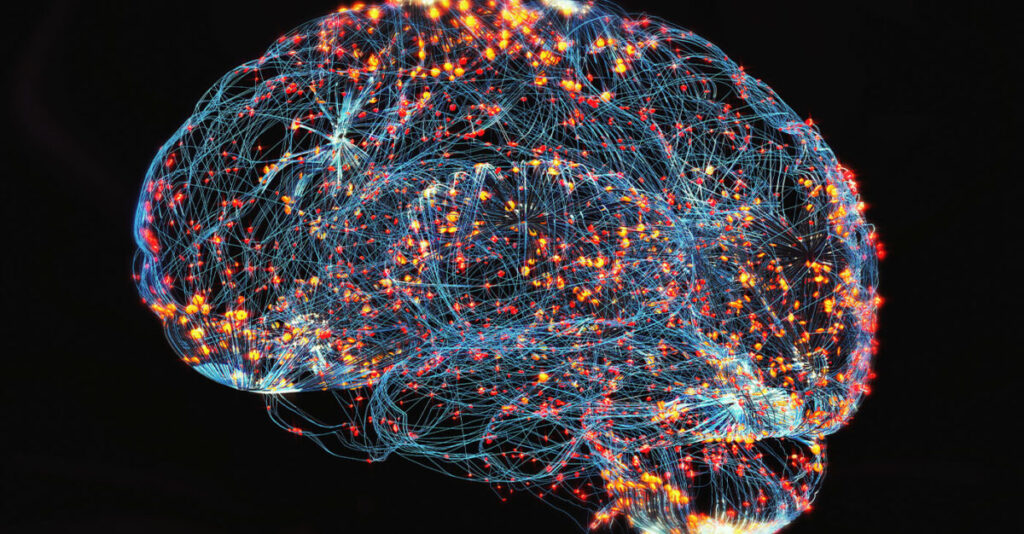

A major clinical trial has found that structured lifestyle changes can lead to greater improvement in brain function for older adults at risk of cognitive decline, compared to less intensive, self-directed approaches.

The peer-reviewed study, titled “Effects of Structured vs Self-Guided Multidomain Lifestyle Interventions for Global Cognitive Function: The U.S. POINTER Randomized Clinical Trial,” was published this week in The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) and presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in Toronto.

It provides a large measure of hope against an illness that has long had many in fear. Researchers enrolled 2,111 participants between the ages of 60 and 79 who were at elevated risk for cognitive decline and dementia due to factors such as sedentary behavior, poor diet, cardiometabolic conditions, and family history of memory loss.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two lifestyle interventions, either a structured, high-intensity program or a lower-intensity, self-guided version, and followed for two years. Both groups focused on improving physical activity, nutrition (through the MIND diet), cognitive stimulation, social interaction, and cardiovascular health.

However, the structured group attended 38 facilitated meetings over two years and followed detailed activity plans, while the self-guided group attended six meetings and was encouraged to pursue goals independently without coaching.

Both groups in the study—those who followed a structured lifestyle program and those who made changes on their own—showed improvement in overall brain function. However, the group that followed the structured plan improved more over the two years. Researchers measured this improvement using a standard scoring method that looks at multiple aspects of thinking, such as memory, attention, and speed.

On that scale, the structured group improved by 0.243 points per year, while the self-guided group improved by 0.213 points per year. The difference between the two groups—0.029 points—was small but statistically meaningful, meaning it’s unlikely to have happened by chance.

The structured group also did better when it came to executive function, which involves planning, decision-making, and self-control. Their scores improved slightly more each year—by 0.037 points—compared to the self-guided group. The structured group also had slightly better scores in processing speed, or how quickly the brain handles information, but that difference wasn’t strong enough to be considered significant. When it came to memory, there was no clear difference between the two groups.

The participants included 68.9% women, and 30.8% identified as part of a racial or ethnic minority group. Thirty percent were carriers of the APOE-e4 gene, a known genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Retention was high, with 89% completing the final two-year assessment. Researchers reported that the structured intervention produced benefits regardless of sex, age, race, cardiovascular health, or APOE-e4 status.

The cognitive improvement was more pronounced in participants with lower baseline cognitive scores. The study was conducted at five clinical sites across the United States from 2019 to 2025, with oversight by Wake Forest University School of Medicine and approval from a centralized institutional review board.

It is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under identifier NCT03688126. “Among older adults at risk of cognitive decline and dementia, a structured, higher-intensity intervention had a statistically significant greater benefit on global cognition compared with an unstructured, self-guided intervention,” the researchers wrote.