By Terri Schlichenmeyer

Your application was accepted.

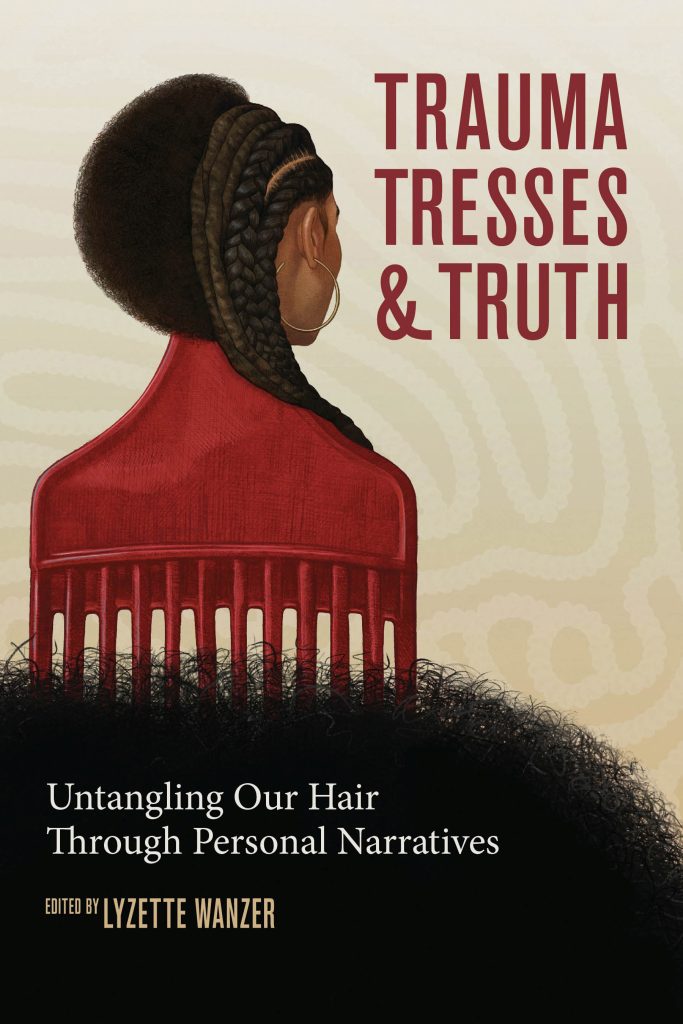

The phone interview went well; the person you spoke with seemed impressed with your credentials, your education and experience. You laughed at the same jokes. Knew some of the same industry people. At the in-person interview, they told you that the job was yours – if you’d change one thing. “Trauma, Tresses & Truth,” edited by Lyzette Wanzer, combs through this irritation.

Nearly four years ago, then-senator Holly Mitchell of California wrote and sponsored what she called the CROWN Act, which prohibits discrimination based on hair style and texture. That summer, California passed the law and since then, other states and municipalities have followed suit. And yet, hassles happen on behalf of hair.

In times of slavery, hair was hidden to “restrict the appearance” of marketable women and to enforce conformity, and preference was given to slaves that had straighter hair and lighter skin. A century ago, advertisements for “hair dressing” promised to tame “kinky, snarly, ugly” hair. The availability of Madame C.J. Walker’s products showed that “Black women… take [their] nappy hair and figure it out.”

Sometimes, though, it feels like “the Black body is a war zone and the Black skull, the helmet.” It happens to men, when people question their braids in professional settings, or they stereotype men with locs. It happens when a white person touches your hair or even asks to touch it. Worst of all, pelo malo (bad hair) are words that follow babies and small children who are too young to shout the word “no” or to choose for themselves.

Sometimes, though, it feels like “the Black body is a war zone and the Black skull, the helmet.” It happens to men, when people question their braids in professional settings, or they stereotype men with locs. It happens when a white person touches your hair or even asks to touch it. Worst of all, pelo malo (bad hair) are words that follow babies and small children who are too young to shout the word “no” or to choose for themselves.

As for work, says one essayist, “A 2017 study confirms that Black women face bias in the workplace when wearing natural hairstyles.” It might happen with lowered tips at a restaurant job, a lack of promotion or a raise, or the loss of a job altogether – and for what?

Says another essayist, “My hair doesn’t do my job. I do.”

A quick flip through “Trauma, Tresses & Truth” suggests that this book isn’t going to tell you anything that’s new. It is, in fact, quite a bit of preaching to the choir, since most people who will pick it up are living it. And yet, there’s appeal in these pages, and support, as though you’ve just entered a town hall meeting for Black women’s hair.

While it’s a fact that men are slightly represented in this book, the essayists that editor Lyzette Wanzer has pulled together are mostly Black and Puerto Rican women who write about earlier hairstyles in a manner that can make you sit back, sigh in remembered happiness, and let your shoulders relax. It’s not all good, though: some essayists recall tender-headed pain, Jheri curl messes, and embarrassment from long ago or last week.

These memories, these exasperations, serve to weave camaraderie into each tale.

Clearly, this is a book for women but Black men may likewise find words that’ll make sense to them, too. If you’re tired of hair harassment, read “Trauma, Tresses & Truth.” It’ll make your toes curl.