By George E. Curry

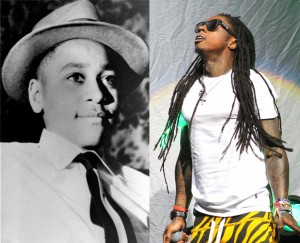

(NNPA) The murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till in 1955 was a watershed moment, marking the beginning of the modern Civil Rights Movement. While visiting relatives near Money, Miss., the Chicago native was murdered for allegedly whistling at a White woman. The brutal act was intended to send an unmistakable message to Black boys everywhere: If you even whistle at a White woman in the Deep South, you could pay for it with your life.

Like everyone else, I was appalled to learn that rapper Lil Wayne had made a vulgar reference to Till’s death. On a re-mix of an upcoming CD by Future called Karate Chop, Lil Wayne essentially spewed the line: “Beat that [female sex organ] up like Emmett Till.”

When I sat down to write this column, I planned to excoriate Little Wayne about his insult. I started to remind him that musical artists don’t have to be ignorant fools, even while showing their underwear on stage. I was going to say that Curtis Mayfield of my era and Chuck D of his generation demonstrated that African-American artists can make good music and provide uplifting race-conscious lyrics at the same time.

Rather than spend another nanosecond on Lil Wayne, we should use this Black History Month moment to educate young people who may not have ever heard of Emmett Till. While serving as editor of Emerge Magazine, I had the pleasure of interviewing Mrs. Mamie Till Mobley, Emmett’s mother. For the 40th anniversary of his death in 1995, I wrote a story on Emmett Till.

This is how it began:

Mamie Till Bradley was about to experience a mother’s worst nightmare. She had to identify the corpse of her only child, 14-year-old Emmett Till, who had been abducted, beaten, shot in the head and tossed into the Tallahatchie River near Greenwood, Miss., for allegedly whistling at a White woman.

As she approached the cold, metal slab that held the mutilated body at A. A. Rayner & Sons funeral home in Chicago, the grieving mother thought to herself: “I got a job to do and it’s not going to be easy.”

Mamie Till wanted to look directly into her son’s face, but she couldn’t bring herself to do it. Not yet. So she started with the lower extremities and worked her way up.

“Those are his feet,” she concluded. The ankles? Yes, those were her son’s skinny ankles. Next, she surveyed the knees. Most people have sharp, pointed kneecaps. But the mother and son had flat ones. “Those are the Till knees,” she told herself.

Her eyes continued up her son’s body and stopped on his genitals. Later, she would be happy that her inspection included that section of her son’s body because some people later would say, incorrectly, that Emmett had been castrated. Now, she would know otherwise.

Mrs. Mamie Till Bradley Mobley — who will be called Mrs. Till hereafter to make it easier to follow the cast of characters in this drama — examined Emmett’s hands and arms, which provided more confirmation of what she did not want confirmed. Finally, she took a deep breath and looked at her son’s decomposed face. This, too, she did piece by piece, separating his face into imaginary compartments, starting with his chin and moving to the top of his head.

“Bo,” as he was known, had flashed a perfect set of teeth during his short life. Now, in death, only one or two were visible. “Oh, my God,” his mother thought. “Where are the rest of them?”

The bridge of his nose, though all chopped up, was recognizable. She looked for his right eye — it was missing. There was only an empty socket. She looked at the left one and it was detached, dangling from the socket.

“That’s his hazel eye,” Mrs. Till said. “Where is the other one?”

She searched for one ear and it, too, was missing. Peering through the ear hole, she could see daylight on the other side. The remaining ear protruded from her son’s head, just like hers— another family trait.

“That’s Emmett’s ear,” she said, softly.

His hair? Yes.

After inspecting the outstretched body inch by inch, Mrs. Till came to the sad but inescapable conclusion that the remains of what remained before her were those of Emmett Louis Till. Still, she turned to Gene Mobley, later to become her third husband, hoping he might have noticed something that she had not, anything that would cast the slightest doubt about whether this was indeed Bo. But Mobley had identified young Till in his mind long before the child’s mother had finished her methodical examination. The barber had recognized the haircut he had given Emmett two weeks earlier, just before Bo left for Mississippi.

Mrs. Till had one thought over and over: What kind of person could do this to another human being, especially a 14–year–old boy?

Her second thought was that this was a sight so ghastly, so inhumane that people would have to see it for themselves to believe it.

“Gene, I want you to go home and get some of Bo’s pictures,” she said. “We’ll spread the pictures around.”

The undertaker politely asked, “Do you want me to fix him up?” Mrs. Till did not hesitate: “No, you can’t fix that. Let the world see what I saw.”

Obviously, Lil Wayne never saw that story. If he had, he would have realized this isn’t something to be taken lightly.

George E. Curry, former editor-in-chief of Emerge magazine, is editor-in-chief of the National Newspaper Publishers Association News Service (NNPA.) He is a keynote speaker, moderator, and media coach. Curry can be reached through his Web site, www.georgecurry.com. You can also follow him at www.twitter.com/currygeorge.