By Lee A. Daniels, NNPA Columnist

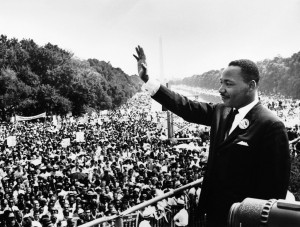

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!”

A suggestion for these days of special attention to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: Whenever people cite this sentence from his iconic “I Have A Dream” speech, ask them if they know the rest of the speech.

I’ve long suspected that people who cite that sentence as proof we today should stop taking race into account in the necessary re-ordering of American society haven’t bothered to understand – or, most likely, even read –the rest of the speech. I think that’s because they’ve adopted the let’s-pretend-race-has-no-meaning stance conservatives have been pushing for the last 30 years – ever since losing their all-out effort to defeat the movement for the King national holiday.

So when people refer to that sentence, ask them to explain King’s also saying to the throng, “I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. And some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality.”

Or, ask them to explain his reminding America “of the fierce urgency of Now … It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. … The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.”

Those are just two of the extraordinary passages in what is a wonderfully complex sermon, full of hidden-in-plain-sight demands and warnings along with its call to our better selves. They and other passages illuminate the true meaning of its most famous sentence – a meaning underscored by the three “dreams” that immediately precede it and the one immediately after it.

Before mentioning his children, King declares that “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’”

He follows this with a “dream” that “one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave-owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood,” and another that “even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.”

And then, after he speaks of his children, he says, “I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of ‘interposition’ and ‘nullification’ – one day right there in Alabama little Black boys and Black girls will be able to join hands with little White boys and White girls as sisters and brothers.”

In other words, King places his dream for all children squarely within the necessity of reforming three states with long histories of horrific state-sponsored and state-aided-and-abetted murders, beatings and other forms of violence that targeted Black children as well as adults.

He uses children as the focus of his dreams not only because children are born without prejudice and fear, but also because their being “able to join hands” at “the table of brotherhood” could only occur with their parents’ acceptance of racial equality. Here, King was speaking directly to ordinary White southerners. Come, he said, for our children’s sake, let us recognize our common humanity.

The White South of 1963 answered two weeks later. On September 15, 1963, members of the Birmingham KKK cell dynamited the Sixteenth Baptist Church just after its Sunday School services had ended, killing four girls – Addie Mae Collins, 14, Denise McNair, 11, Carole Robertson, 14, and Cynthia Wesley, 14 – and wounding 20 others. In the maelstrom that enveloped the city that day, two Black teenaged boys who were not members of the church were shot to death. Virgil Ware, 13 was killed by two White male teenagers. Johnny Robinson, 16, was shot in the back of the head by a state police officer.

The Black freedom struggle in the South went on.

So, this Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, when people only reference the Dream Speech’s “the content of their character” line and let it go at that, you’ll know they’re just whistling “Dixie.”

Lee A. Daniels is a longtime journalist based in New York City. His essay, “Martin Luther King, Jr.: The Great Provocateur,” appears in Africa’s Peacemakers: Nobel Peace Laureates of African Descent (2014), published by Zed Books. His new collection of columns, Race Forward: Facing America’s Racial Divide in 2014, is available here on amazon.com