By: Terri Schlichenmeyer

By: Terri Schlichenmeyer

Your hands were clean.

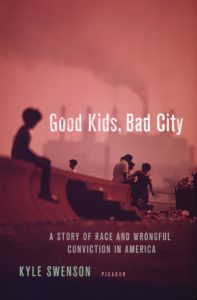

Freshly washed, not a speck of dirt, they were as clean as your conscience. You did no wrong; instead, you promoted what was good and right. But in “Good Kids, Bad City” by Kyle Swenson, past actions sometimes don’t matter.

Over a decade ago, somewhere near Kyle Swenson’s desk at a Cleveland-area weekly newspaper, letters piled up from prisoners begging for journalistic investigation of denied crimes. Like many newsfolk, Swenson was skeptical of those vows of innocence, so he dismissed the letters and others like them. Still, because he was fresh out of ideas for his monthly feature story, he agreed to meet someone to talk about a crime that happened before Swenson was even born.

Kwame Ajamu arrived with a box of papers that shocked Swenson to his core.

On May 19, 1975, as Swenson learned, salesman Harry J. Franks was collecting from his accounts when he was shot and killed on a Cleveland sidewalk. Coming home from a pick-up basketball game, Ajamu, Wiley Bridgeman, and Rickey Jackson pushed into a surrounding crowd and saw the white man bleeding on the concrete, but they didn’t stick around. The situation seemed under control. Franks was dead; there was no reason to linger.

They hadn’t been there when Franks was shot, but on May 25, Bridgeman, Ajamu, and Jackson were arrested and charged with murder on the basis of a false account given by a 12-year-old boy, a lie that folded into more mistruths encouraged by corrupt police. Jackson, Ajamu, and Bridgeman swiftly went to trial and were ultimately sentenced to death. Their sentences were later commuted to life.

Released in 2003 after making parole, Ajamu had “talked about his case to anyone who would listen” but no one believed him. That changed in 2011, when a lawyer suggested he take his story to a newspaper reporter.

They arranged to meet at a coffee house. Ajamu “was nervous.”

“That’s when,” says Swenson, “I walked through the door.”

That sentence reads as though it should have a cape and SuperPowers, doesn’t it? But no, there’s much more to “Good Kids, Bad City” and author Kyle Swenson was merely a catalyst: he was the listener Kwame Ajamu needed.

To help readers better understand the subtleties of this tale and its full impact, Swenson shares the history of Cleveland, Ohio, a highly progressive city nearly two centuries ago but one that slowly fell victim to racism further complicated by corruption. Thorough accounts put things into keen perspective here, especially when we’re invited into the homelives of the accused men and their families and we get to know the men as boys. And yet, even with those once-happy sightlines, this story might’ve been just another tale of wrong accusations, except for one thing: Swenson also tracks the accuser, the boy, as he grows up.

That story-within-a-story mushrooms in a way that you’ll want to see. It’ll outrage you as it fascinates. It’s a draw that makes “Good Kids, Bad City” a book to get your hands on.