By Dale Okorodudu, M.D., UT Southwestern

An unpleasant experience I had many years ago on an airplane initially left me angry. But it has since come to shape my thoughts on race and how increased diversity in the medical profession could influence the way white Americans view black men like me.

When I was 20, I boarded a flight from St. Louis to Houston for a trip home from college. The temperature was cool, so like a typical student, I was wearing sweatpants and a hoodie. Shortly after finding my seat, a middle-aged white woman sat next to me.

We exchanged pleasantries, as strangers on a plane often do. But then, over the course of the two-hour flight, this woman began to belittle me. She criticized the way I was dressed and told me that I didn’t speak well. What stuck with me the most was when she said, “Nobody will ever take you seriously. You’ll never be successful.”

I remember asking myself: Is this what some people think when they see a person who looks like me?

I’ve often reflected on that unusual encounter, wondering what would prompt a person to act that way. Clearly, my seatmate saw a young black man in a hoodie as a hopeless failure, not as a person who would become a doctor in a few years.

I suspect that she had had limited interactions with black men over the course of her life. Since then, I have come to believe that if more people got to know successful black professionals, outlooks would change.

Bias and racism begin to develop in children as early as age 5. As they become aware of race, they make associations based on how people look. Negative parental attitudes can make children wary and judgmental of people who look different from them; the lack of positive minority imagery in the media only adds to the problem.

Misperceptions of black men persist among individuals who have little real-world contact with them. I’m willing to bet that when many Americans close their eyes and imagine a black man, what comes to mind may not be the most positive picture. But it should be. The truth of the matter is that most black men are people with normal jobs and lives like everyone else. Yet that’s difficult for someone to appreciate if they don’t see them regularly.

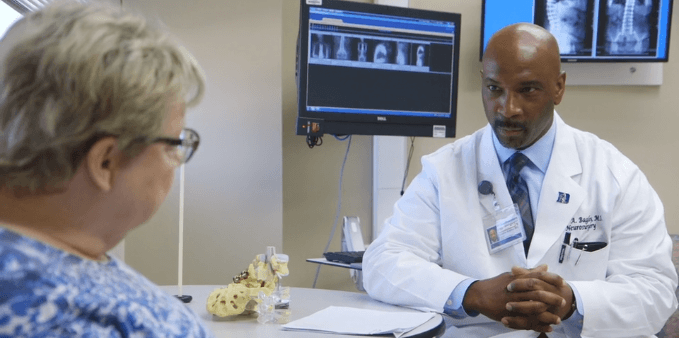

Being cared for by a black male doctor can change this narrative. I see this almost every day at work. When children watch their mom or dad speak with me, they see that their parent respects me. The doctor-patient relationship also builds a special trust. I still vividly remember encounters with my own childhood physician, Dr. Nina Miller, a white woman I revere to this day.

Unfortunately, the chances of seeing a black male doctor in the U.S. are slim. Black men have historically been underrepresented in the medical profession, comprising only about 2 percent of U.S. physicians. And the number of black male applicants to medical school has not been growing. According to a report from the Association of American Medical Colleges, the number of black male applicants to medical schools was actually lower in 2014 than in 1978.

This discouraging trend may have consequences for the health of the black community. A study published last year by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that black men, who have the lowest life expectancy of any ethnic group, are more likely to follow preventive health recommendations when they are seen by black doctors.

To reverse the trend of declining black men in medicine, we need to convince more black boys to pursue careers in the field. Several years ago, I launched “Black Men in White Coats” to inspire more of these individuals to consider medicine as an occupation. It is a series of videos featuring black physicians from my medical school, UT Southwestern, and others who shared stories and perspectives on how race has influenced their careers. We hope these testimonials will show young people that with hard work and dedication they can overcome obstacles and become the positive role models our society needs.

I wish every child had the opportunity to be cared for by a black male doctor. They would come to trust and respect this person and, early in life, develop a personal and positive relationship with a black man. Maybe then more people would understand that individuals who look like me, no matter what they’re wearing, are likely to be sincere, intelligent, and loving.

Dr. Dale Okorodudu is a pulmonary and critical care physician and an Assistant Professor at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. He is the founder of DiverseMedicine Inc. and the author of “How to Raise a Doctor: Wisdom From Parents Who Did It.”