By Terri Schlichenmeyer

Your mom was always on your side.

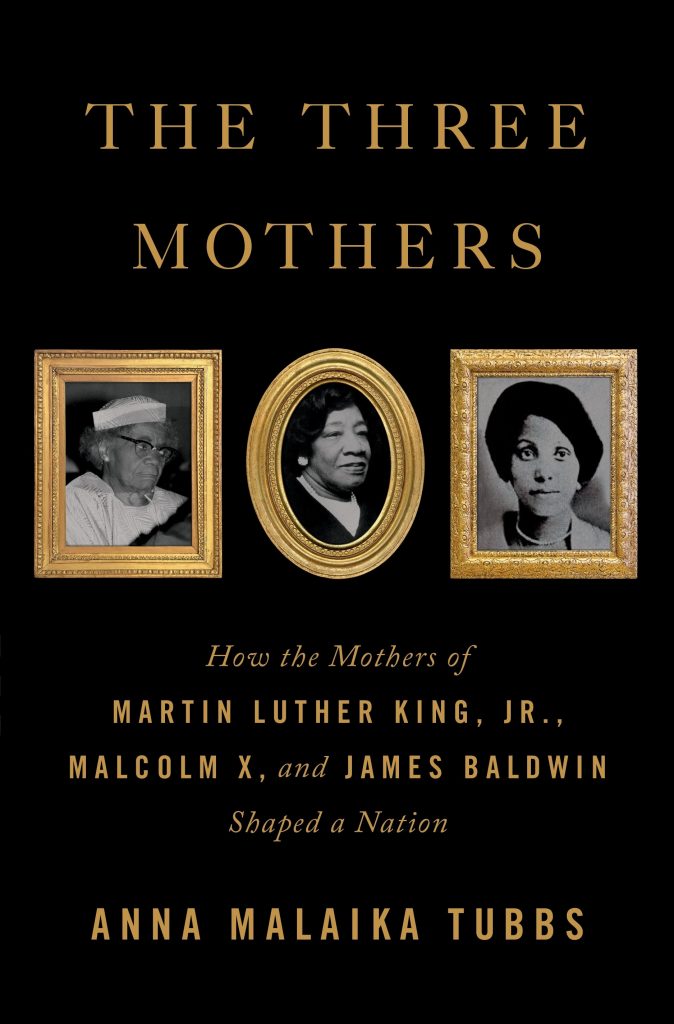

She stuck up for you when nobody else would, through thick and through thin. She had your back, she prayed for you, and she wanted the best for you. She was always there and that never changed, though in the new book “The Three Mothers” by Anna Malaika Tubbs, some mothers change the world.

For most of her life, Louise Langdon hated the color of her skin.

Growing up in Grenada in the late 1800s, she was surrounded by the dark-skinned children of former slaves but Louise‘s father was a white man who raped her barely-teenage mother, leaving Louise with a pale complexion. For the rest of her life she held deep anger at the supremacy that white people assumed, from her migration north to her marriage to Earl Little and her activism, the latter of which she passed to her son, Malcolm.

Growing up in Grenada in the late 1800s, she was surrounded by the dark-skinned children of former slaves but Louise‘s father was a white man who raped her barely-teenage mother, leaving Louise with a pale complexion. For the rest of her life she held deep anger at the supremacy that white people assumed, from her migration north to her marriage to Earl Little and her activism, the latter of which she passed to her son, Malcolm.

As a part of the Great Migration, Berdis Jones got caught up in the excitement of the Harlem Renaissance and some months after landing in New York City, Berdis gave birth to a son whose father was uninterested. For much of young Jimmy‘s early life, then, it was just him and his mother, and she worked long nights at a cleaning job to ensure that he had what he needed. What he didn’t need was a new stepfather, David Baldwin, who suffered from an undiagnosed mental illness.

The Reverend and First Lady of Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church wanted only the best for their daughter, Alberta. The Williams gave Alberta the finest education, music lessons, all that an upper-class Black young lady would need. When an itinerant, uneducated preacher, Michael King, came calling on Miss Alberta, the Williams were dead-set against the romance. Alberta, however, saw a good heart in Michael – one that later inspired their son, Martin.

“The Three Mothers” is one of those books that you really want to like but doing so is a challenge. It’s a very good book that’s in very bad need of an editor.

Format-wise, it starts where all good biographies do. Author Anna Malaika Tubbs tells why she wrote this book before she plunges into a brief account of the ancestry of her main subjects. This immediately begins to build the layers of story that ultimately explain the work behind three great men.

At issue, however, is that each section of the women’s lives is woven very loosely around Black history of their era. That contributes to a confusion of timeline, and out-of-place points that reduce the smoothness of a history that’s otherwise riveting. It’s like trying to watch three TV shows at once; add contradictions and a confidently-stated point-as-fact that experts still aren’t sure about, and you may be left frequently scratching your head.

If you overlook the scatteredness and don’t mind frequent side-trips, “The Three Mothers” is a great examination of a rarely-told triple story and you’ll love it. If you like your books more linear and straightforward, though, just put this one aside.