By Terri Schlichenmeyer

Tis the season of giving.

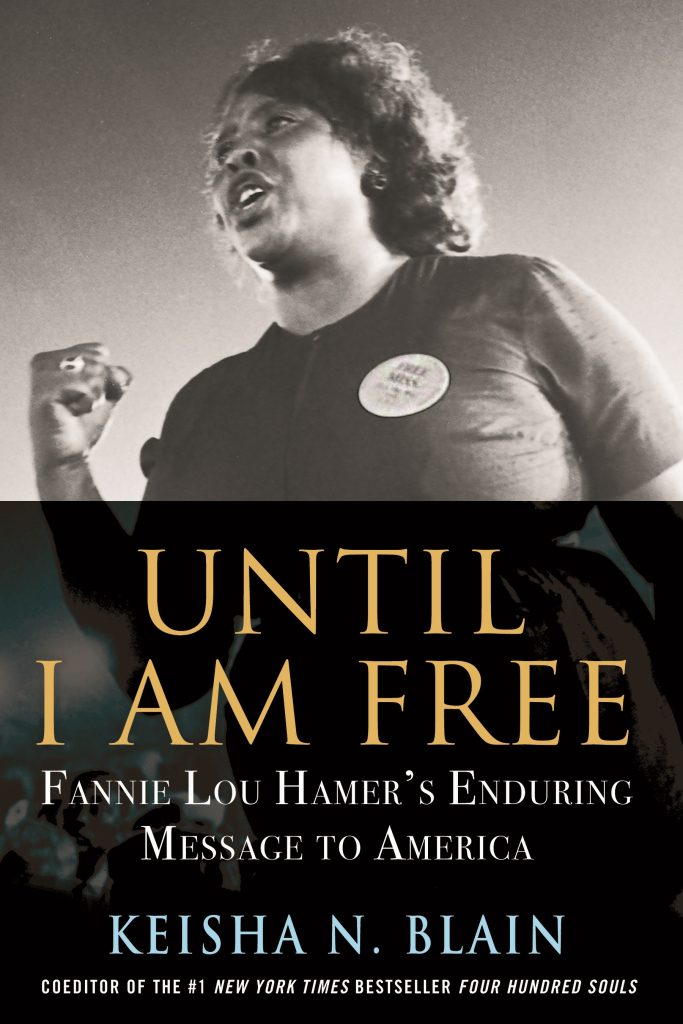

A few coins in a bucket, folded dollars in an envelope, an extra donation to the church, you don’t mind. Wrap a small gift for a child in need, give to someone who has nothing, it’s the holidays. Or read “Until I Am Free” by Keisha N. Blain, and give of yourself.

From the day she was born in Mississippi in the fall of 1917, Fannie Lou Townsend knew only poverty. She was the youngest of twenty children, and her parents were mostly sharecroppers; because they needed every pair of hands to keep ahead, Fannie Lou often stayed home from school to help, beginning right at age six.

As a younger woman, Fannie Lou stayed on the same plantation where she was born and though she seemed to live a quiet life, there were hints of mid-twentieth-century scandal: documents show that she may’ve been wedded to a man named Gray before marrying Percy “Pap” Hamer in 1944. She never birthed any children; it’s said that she tried to, but was sterilized without her permission in 1961, a fact that she learned fourth-hand.

The following year, says Blain, Hamer “found her calling” when she attended a meeting through her church, with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). It was an important event: instantly, Hamer saw how voting could give Black citizens better opportunities and better lives through their ballots. For the rest of her days, Hamer worked for civil rights, teaching and speaking with an emphasis on the Constitution.

The following year, says Blain, Hamer “found her calling” when she attended a meeting through her church, with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). It was an important event: instantly, Hamer saw how voting could give Black citizens better opportunities and better lives through their ballots. For the rest of her days, Hamer worked for civil rights, teaching and speaking with an emphasis on the Constitution.

She was a big proponent of letting people decide their own political futures locally, without interference. She promoted leadership within the Black community, working for the future of all, and especially Mississippi. Hamer was not a feminist but she was fierce about empowering women. Almost right up to the day she died of breast cancer in 1977, she was an activist and advocate…

In her introduction to this biography, author Keisha N. Blain wonders why the name of Fannie Lou Hamer doesn’t often stand in the company of Dr. King, Rosa Parks, John Lewis, and Angela Davis. In “Until I Am Free,” Blain fixes that omission.

Though it’s often repetitious, Blain’s account of Black life in the Jim Crow South is important – maybe more so because she leaves none of Hamer’s personal stones unturned. This makes for a very good portrait of Hamer, but biography is only half the story.

Using today’s headlines as a frame for Hamer’s life, Blain shows readers how events from the past still resonate today. She also lets us imagine what Hamer’s outrage might be like over Philandro Castile, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Sandra Bland, and George Floyd by tying their deaths to the mistreatment that Hamer endured through her childhood, during her rise in activism, and beyond.

For younger readers, that could be an important part of their education. “Until I Am Free” will be a great inspiration for you, if you’ve never heard it before. This time of year, it’s also a good book to give.