By Terri Schlichenmeyer

One step ahead, three steps behind.

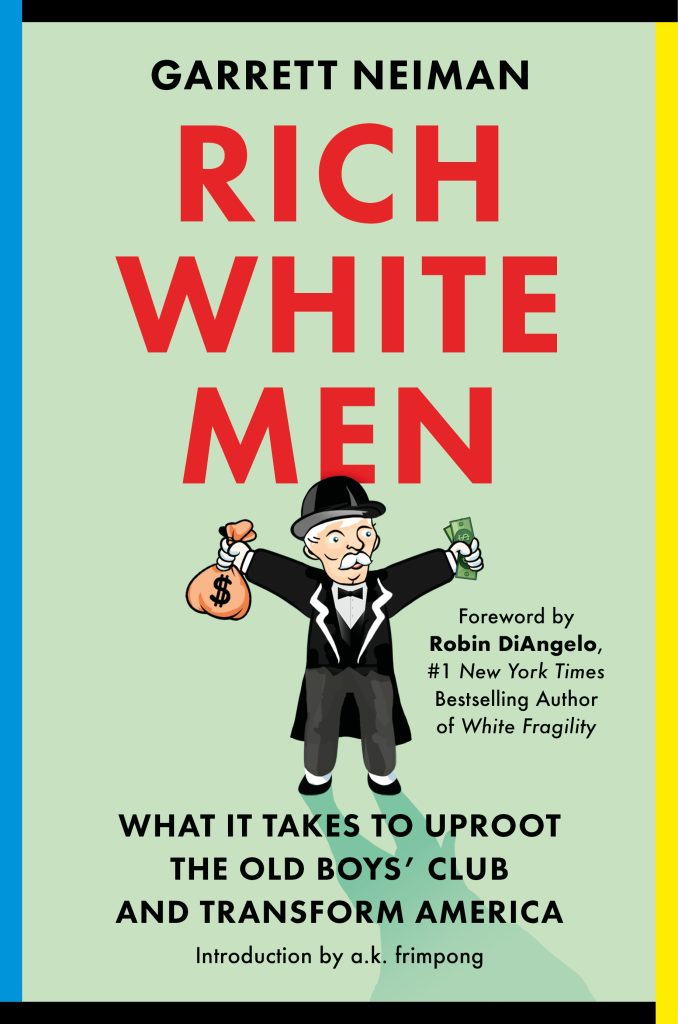

That’s how your life feels sometimes. You make movement forward and something comes along to push you back to where you were two weeks ago. Progress is made, and just as quickly taken away. You get to where you need to be, and you’re clawed back. Welcome to the real world and, as in the new book “Rich White Men” by Garrett Neiman, come meet the culprit.

Six years ago, at a summer retreat for the nonprofit that he’d founded, Garrett Neiman felt certain that his organization – one that served students of color who wanted to attend college – reflected the diversity of its clients. His staff, though, saw things differently. They emphatically told Neiman where he could do better.

He was devastated and, seeing how white privilege affected his work, he vowed to make changes. White privilege, particularly within a patriarchy, he suggests, is the root of inequality at work and at large.

Equal opportunities do not equal outcomes, Neiman says, and the distribution of wealth today goes back more than two centuries. Bias and bigotry, whether overt or subconscious, play a part in the way things are, and that sometimes extends to stereotypes in the kinds of work non-white, non-male, non-cisgender employees are assigned to do. Tokenism hides the problem, and pretending that the past has no bearing on today only exacerbates the issues.

For sure, “Rich White Men” seems earnest and very well-meaning. Author Garrett Neiman begins with a confession that obviously plagues him, and he vows to do better in a category that’s important to him. This book, alas, isn’t quite it.

It’s very helpful that Neiman looks at all aspects of white male patriarchy in finance, real estate, and industry – but for BIPOC, LGBTQ, and female readers, it’s preachin’ to the choir. It’s great that he factors in the generally unfactored, including the tiniest details that sometimes go unnoticed, but again: the choir.

The argument could be made that white, wealthy men might read this book and make changes, but the tone of it seems to doubt that possibility. Advice on moving things forward is hard to find and clear-cut help is in here, but it’s scarce.

There are a lot of personal tales inside this book, and a propensity to nickname transgressors (and then explain the nicknames!), both of which are rather irrelevant and may just irritate some readers. Yes, “Rich White Men” might be of some help, or you may want to set it behind you.