By Terri Schlichenmeyer

Your skin was not even broken.

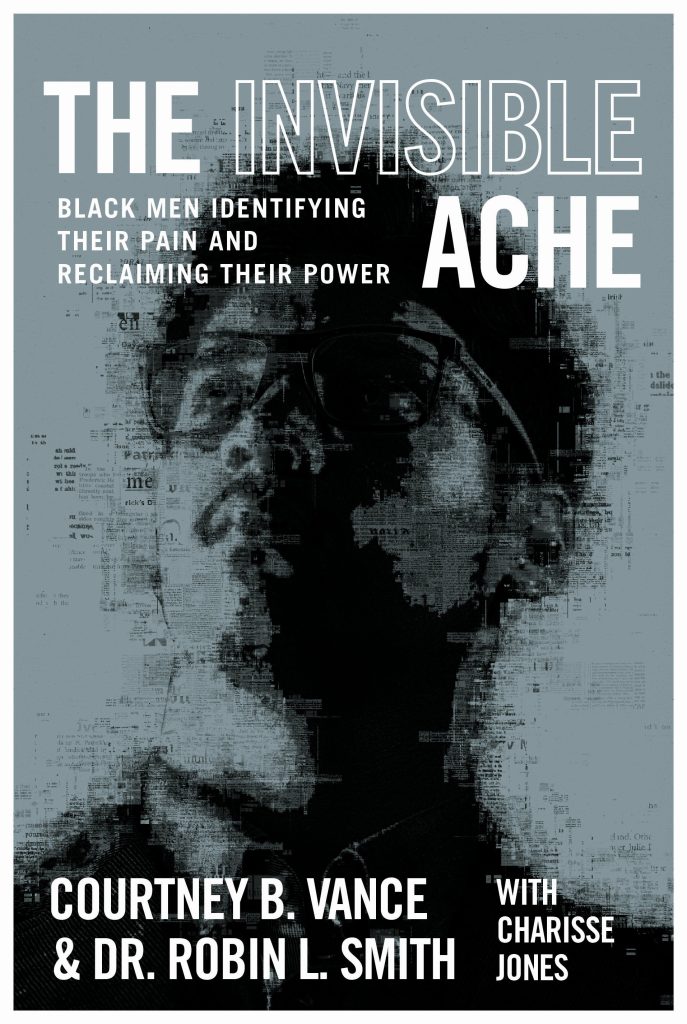

No cuts, no scratches, no stitches needed. There was no blood and no bruise, either, not even the least bit of soreness. And yet, you’re wounded, raw, wincing. You’re absolutely not okay right now, and in the new book “The Invisible Ache” by Courtney B. Vance & Dr. Robin L. Smith, with Charisse Jones, it’s from a hurt you cannot see.

The phone call came early in the morning in the middle of the week.

Courtney Vance’s father had taken his own life, leaving his adult children and a wife who was all but paralyzed with grief. Vance “felt like a boy suddenly dealing with big man stuff” but he helped his mother who, after the funeral, insisted that Vance and his sister seek therapy.

Says Vance’s co-author, “Society’s mirror doesn’t reflect how varied Black men really are…” Black boys are not supposed to cry or be vulnerable, although Smith says that “To be vulnerable is to be strong.” Black men are taught to deal with their problems alone, in silence, but Smith says that talking through trauma allows room for reclaiming power.

Seek support, she says, and remember that “life isn’t virtual,” so draw boundaries and step back from social media sometimes. Don’t be afraid “to talk to young men [and] young women, about the sanctity of their bodies.” Find your sense of gratitude and remember that church isn’t the only place to pray.

“Feel free to frolic. Walk barefoot through a mud patch if it makes you happy. Plant a garden. Pick up a hula hoop. Plunge into a pool.”

And remember: when it comes to mental self-care, “silence isn’t golden. It is actually deadly. So let’s talk it out.”

Have you hit your discomfort level yet? If not, well, just wait. Authors Courtney B. Vance and Dr. Robin L. Smith will take you there soon enough – and in “The Invisible Ache,” they’ll bring you back whole.

Part autobiography, part advice, this book is like getting poked and prodded until a deep self-inspection is performed – and then being asked to look again. It’s very raw, like removing the bandages the day after cutting off a piece of yourself, but it’s oddly cathartic.

Vance tells his tale and that of his father in a calm way that makes readers want to keep going, despite that it hurts; Smith then takes over and soothes the pain with leading statements that feel like having your hand held. It’s a nice mix, and very helpful.

While this book is primarily meant for Black men, young and old, it’s not a bad read for a woman who wants to help, understand, or do some introspection of her own. Find it; “The Invisible Ache” is not just for the broken.