By Terri Schlichenmeyer

No disrespect meant.

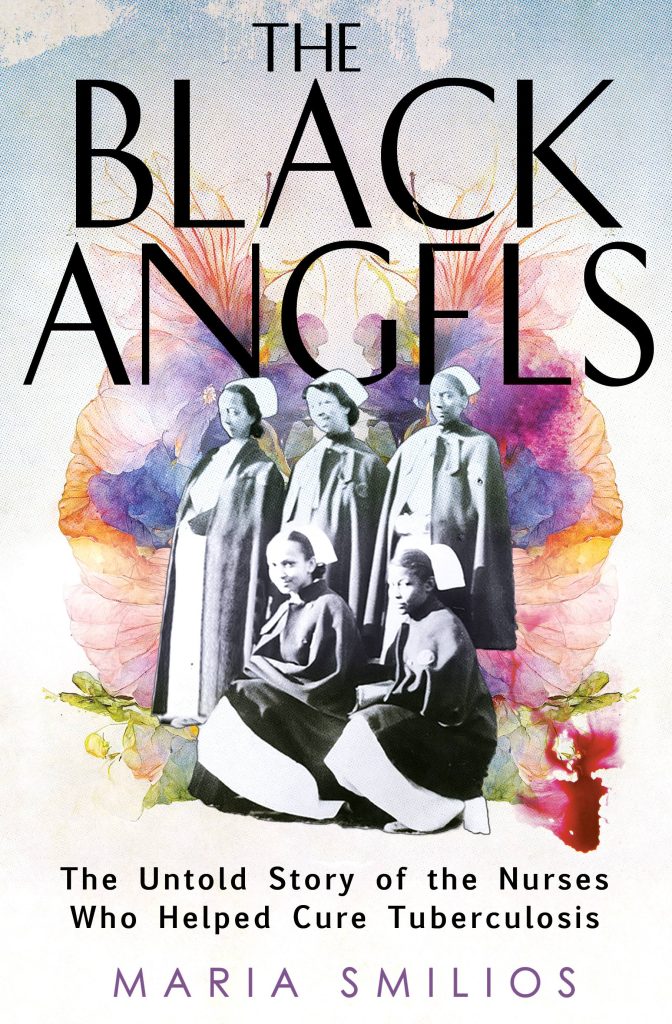

You won’t tolerate it anyway, so that’s a good thing. As a human being, someone who walks and talks, forms ideas and creates concepts, you absolutely, righteously demand that others give you the respect you want. The respect you deserve. Even if, as in “The Black Angels” by Maria Smilios, getting it takes decades.

Edna Sutton hated her job sorting papers in a downtown office.

True, it didn’t require housekeeping or service, as did most jobs for Black women then, and she appreciated that. She wasn’t interested in being someone’s maid; instead, science “set her mind alight,” and Edna dreamed of becoming a nurse. She would only be allowed to work in a Black hospital, though; and there weren’t many of those in Savannah, Georgia.

In early 1930, she became a part of the Great Migration when she boarded a train to Harlem.

For decades, Edna Sutton and her fellow Black nurses did the work that white nurses would not do, tending to the poorest of the poor who often came from overcrowded tenements to Sea View on Staten Island. Sanity was a wish for those nurses: hand-washing was stressed, but masking was not. Sometimes, masking was frowned-upon.

Some were reminded the hard way that tuberculosis was airborne and highly contagious.

And yet, despite long hours and putting themselves in constant danger, raises and promotions were out of reach for the Black nurses, mostly due to Jim Crow laws. They striked, to no avail; the NAACP urged New York City’s mayor to change the law, but he dragged his feet.

To gain respect and recognition, the nurses would need “something huge… something like a war.” With their help, a cure for tuberculosis would take even longer…

Imagine a disease that you can catch from a cough or sneeze, one that steals your ability to breathe and puts you in the hospital, gasping for air and grasping at life. The story of that disease is a big part of a hidden history, and not just déjà vu.

Knowing what we know about pandemics, in fact, makes “The Black Angels” feel closer to home, and it makes the personal and medical sacrifices of Edna Sutton, Missouria Meadows-Walker, and Virginia Allen feel larger. Read, and recent events bring a sense of dread to the tale. Read, and you’ll know the frustration involved. Author Maria Smilios then casts a wider story net that takes readers to the periphery for further understanding, to two world wars, to Harlem, medical research, and the political atmosphere of New York, 1945.

Beware: the extraneous coverage goes deep and it may distract from the larger story of Black heroism and history. Go with the dive, though, and you’ll find that “The Black Angels” is a pretty respectable read.