“In wildness is the preservation of the world.”

—Henry David Thoreau

Lately, the news has been a slow wrecking, a bruise spreading beneath the skin of the day. But nothing has broken me like the thought of America’s parks, forests, and wildlife—waiting, unknowing, on the edge of disaster.

I have not spent weeks backpacking through Yosemite, nor have I traced the rim of the Grand Canyon at sunrise, waiting for the first light to break over the red rock. I have never stood beneath the ancient arms of a Sequoia and pressed my palm against its bark, though I imagine it would feel like touching something older than language. And yet, the loss of these places—the slow, bureaucratic undoing of them—feels personal, as if something I had always believed in without needing to see is being quietly taken away.

I have loved the land of this country in the way one loves a distant ancestor, with reverence, with awe, with the deep understanding that something about it is in you whether or not you have stood in its presence. This is a complicated love, because I have feared and loathed this nation in equal measure. To be Black in America is to know that the country itself is not for you, that it was built on your physical, emotional, mental, spiritual, and creative labor but never with your freedom in mind. And yet, the land is different. The land does not ask for loyalty, does not demand allegiance. It belongs only to those who honor it, who care for it, who kneel in the dirt with open hands rather than raised fists. The rivers do not remember the chains, but they remember those who have waded through them with reverence. The mountains do not care who claims them, but they open themselves to those who tread lightly, who listen.

I don’t know whether I have ever truly believed in America as a promise, but I have believed in its rivers and canyons, its mountains and forests—because the land, at least, keeps faith with those who keep faith with it.

My reverence for the land began, as many things do, in childhood. I watched The National Parks: America’s Best Idea on PBS, Ken Burns’ sweeping meditation on the country’s wild places. The slow pan of archival photographs, the grandeur of John Muir’s (although, he was a racist) words read in reverent tones, the black-and-white footage of the early rangers who believed in something larger than themselves—it all embedded itself in me. The parks were a kind of myth, a story America told about itself that, for once, did not feel like a lie.

But it wasn’t just the national parks. I watched The American Buffalo, another Ken Burns masterpiece, and saw the way the land itself had been shaped by survival, by greed, by loss. I saw how an entire species was driven to near extinction because of conquest, because of the impulse to control and own, to strip the wild of its autonomy. I watched The Dust Bowl, listened to the voices of those who stayed as the land dried and cracked beneath them, who watched the very earth rise up against them in storms that turned the sky black.

One thing was undeniable to me watching these documentaries: the best thing about America is this land. Not its mythologies, not its proclamations of freedom, not its self-congratulating declarations of justice. The land. Because despite all of this country’s ugliness—its wars, its cages, its lies, its insatiable appetite for suffering—the land remains greater than the sins of its supposed owner. It is the one truth America cannot corrupt, though God knows it has tried.

What Ken Burns’ documentaries helped me come to begin understanding is that before America was a country, before it was a map drawn and quartered by men who named rivers after themselves, before borders and deeds and state lines, it was land. Just land. A vast, breathing thing—mountains rising like the backs of sleeping gods, rivers cutting veins into the earth, prairie grasses bending beneath the weight of wind. There was no West, no East. There was no middle. There was no Texas, no New York, no California, no Florida. There was only land, endless and whole.

And there were those who knew how to belong to it. The Lakota, the Apache, the Diné, the Haudenosaunee. People who read the sky the way others read scripture, who moved with the rhythm of the seasons rather than against them. The land was not property to them. It was a living thing, a mother, a history that stretched beyond memory. There were fires set with intention, rivers approached with ceremony, herds moved with care so that they would return, so that they would not fear the hands of those who shared the earth with them. The land was a covenant, and it was honored.

Then came the taking. The treaties written to be broken, the borders drawn in blood. The rivers were dammed, the forests cut to stumps, the buffalo driven to their bones. And yet, in the aftermath of conquest, in the brutal efficiency of Manifest Destiny, there remained a sliver of restraint, a moment where the victors, having seized everything, paused long enough to look upon what they had not yet destroyed and decided, perhaps, that not all of it should be turned to dust.

The national parks, they tell us, were created to preserve America’s most beautiful places. This is the story, the myth of preservation, the thing Ken Burns made into poetry. But what they do not tell you—at least, not loudly—is that these places were not empty when the first park signs were hammered into the ground. They do not tell you that Yellowstone was cleared of the tribes who had lived there for thousands of years, that the Blackfeet were forced from Glacier, that the Yosemite Valley had been home to the Ahwahneechee long before John Muir ever waxed poetic about its cliffs. The creation of the parks was not merely conservation; it was erasure, another line in the long ledger of displacement, another way the government turned its sins into monuments.

And yet. And yet.

Despite this history, despite the brutal contradictions, the land remains. And for all its exclusions, for all its violences, the parks have become a place where people go to feel small, to remember that they are not the first nor the last, that there is something older than us and beyond us, something not yet ruined. Even those who have never stepped foot in these places—those who have only seen the photographs, the sweeping cinematography of a PBS documentary—can understand the loss that would come with their absence.

But, here we are. Watching it happen in real time.

The numbers are precise, bureaucratic, devoid of poetry: 1,000 National Park Service employees gone, 3,400 from the U.S. Forest Service dismissed. The kind of cuts that are passed off as efficiency, as a trimming of the fat. Trump’s people say it is necessary, that the government is bloated, that the country must learn to live lean. Elon Musk, who now largely oversees such things, as a non-elected official, calls it “streamlining.” The headlines call it a “reduction in force.” A thousand rangers is not a reduction—it is a gutting.

And that is how it begins. Not with a sweeping declaration, but with a slow erosion. A missing ranger here, an untended trail there. A wildfire spreading just a little faster than it would have if anyone had been there to clear the brush. A wilderness meant for all of us, sold in pieces.

The devastation is not immediate, which is what makes it so insidious. The trees do not fall overnight. The rivers do not run dry all at once. Instead, the decay moves like a whisper, quiet enough that most will not notice until it is too late.

Trump, Musk, and the new architects of America, know that if you do not close the parks outright, if you do not announce that the forests are officially for sale, people will not protest. They will not notice the missing rangers, the visitor centers with their doors locked, the trails left to disintegrate underfoot.

I try to imagine the empty stations, the ghostly quiet of a ranger’s desk that will not be filled again. The park rangers have always been caretakers of a country that does not deserve what they protect. They have been the ones to clean up after the reckless, to patrol the backcountry in the dead of winter, to retrieve the bodies of those who underestimated the wilderness. They have told us the stories, taught us the names of the trees, pointed out the tracks left in the mud by creatures we are lucky to glimpse. And now they are being told they are unnecessary.

There is no great villain monologue in this. There is just a Department of the Interior memo stating that cuts are necessary to “reprioritize resources.” There is a White House statement about eliminating waste. There is a billionaire with a Twitter account mocking those who care, posting something about how Dogecoin will buy more land than the government ever could.

And what happens when there is no one left to stand between the parks and those who would claim them for profit? What happens when the roads crack and the trails wash away, when the seasonal firefighters are gone, when the invasive species creep in unchecked? It does not take long. Neglect begets ruin. A thing left unattended will not remain as it was when other humans batter it.

The truth is, this was always the plan. The budget cuts are a prelude, a quiet hollowing-out, a way to make the parks seem unsustainable, their upkeep too costly, their necessity debatable. The government trims just enough from the bones to let the rot set in, and when the foundations start to crumble, they will say the only answer is to sell off the ruins. They will not say it outright, not at first. Instead, they will issue statements about “public-private partnerships” and “leveraging private investment.” They will frame it as rescue rather than theft, a benevolent intervention from oil companies and venture capitalists, all eager to help preserve the wilderness—so long as they can drill beneath it.

If this feels familiar, it is because we have seen it before. Reagan’s Interior Secretary, James Watt, spoke of opening federal land to private industry. The Bush administration approved leases for oil drilling on land that had been untouched for millennia. Bill Clinton, for all his sweeping gestures of conservation, also pushed for increased oil and gas drilling on public lands, greenlighting extractive leases in Montana and Utah, hedging between environmental protections and industry profits. The Trump administration’s first term attempted to shrink Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante, to auction off land that had long been contested but never truly ceded.

It is a pattern that repeats itself, a cycle as predictable as the seasons: first, the funding is cut. Then, the land is declared mismanaged, abandoned, unsustainable. Then, the corporations arrive, claiming only they have the means to salvage what the government has let fall apart.

I think of the other losses, the ones stacking up in this moment. The unraveling of human rights. The erosion of truth. The brutality carried out in real time, pixel by pixel, clip by clip, until we can hardly tell which horror happened yesterday and which one is coming for us tomorrow. The world feels like it is breaking in a thousand places at once, and still—this, too, feels like a breaking.

Because if the parks go, if the wild is left to decay, if the land is finally, fully taken—what is left? What remains of this country that has so little to redeem it beyond its rivers and mountains?

I think about what it means to live in a country that no longer believes in beauty. A nation that sees its greatest inheritance—the land, the quiet, the unclaimed wild—as something to be sold for scrap. A society that does not recognize the sanctity of the rivers and mountains is a society that does not recognize the sanctity of anything. There is no distinction between the gutting of the parks and the gutting of education, the gutting of healthcare, the gutting of basic decency. The same impulse drives both: a belief that nothing has value unless it can be owned, extracted, turned into capital.

What happens when a country loses faith in itself? Not in its mythologies, not in the fictions it tells itself about its own greatness, but in the one thing it had that was real? This was never a great nation. But it was, at the very least, a vast one. It had land that stretched beyond the imagination, land that could humble even the most arrogant, land that, if you stood in it long enough, might let you forget, for a moment, that human hands had carved it up into something smaller.

The loss will not be immediate. It will not come with a great proclamation. That is not how things are lost in America. They are lost slowly, in the margins of the budget, in the footnotes of policy memos, in the bureaucratic language of efficiency and streamlining. But not yet. Not if we refuse to look away. Not if we decide the land is still ours to defend.

It is not just the land that is being lost. It is the idea that there are things in this country that should exist beyond the reach of capital, beyond the logic of profit and ownership. That there are spaces meant for nothing but sky and silence. That there are places where no one has to buy a ticket, where no one has to be convinced of their worth. That there is land that simply is.

That idea is vanishing.

There will be those who say it was inevitable. That America cannot afford such indulgences, that in times of crisis, beauty is a luxury, wilderness an excess. But this is not excess. This is what remains when everything else has been taken. This is the last, best thing.

If we let it go, we will not get it back. Not in our lifetimes. Not in our children’s. But there is still time. The trees have not yet fallen. The rivers still run, though they do not know what is coming for them. The land does not belong to those who would ruin it—it belongs to those who will fight for it.

So we cannot let it go. We cannot let them gut the parks in silence, cannot let them carve up the land while we are too distracted, too weary, too full of our own small disasters to fight for what is still here. Call your representatives. Show up at meetings. Donate to the organizations that are fighting to keep the land from being stripped to its bones. Visit the parks, walk the trails, bear witness while there is still something to witness.

And when they tell you the land is no longer ours, remind them: it never was. It belongs only to those who honor it. And we are still here. And we are not done.

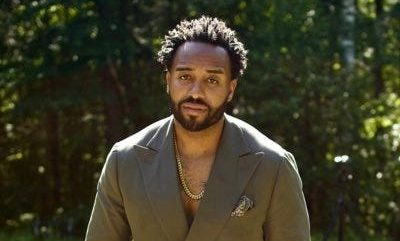

Frederick Joseph is a Yonkers, NY raised two-time New York Times and USA Today bestselling author. His books include a poetry collection, We Alive, Beloved, two books of nonfiction, Patriarchy Blues, and The Black Friend, a collaboration, Better Than We Found It, and a children’s book, The Courage to Dream, Black Panther: Wakanda Forever.

His substack is available at https://frederickjoseph.substack.com/.

Joseph’s books have been named an Amazon Editors’ Pick, notable by the International Literacy Association, Best Children’s Book of the Year by Bank Street College, a Cooperative Children’s Book Center Choice selection, nominated for the In The Margins award, Booklist Editors’ Choice, a Notable Trade Book for Young People by the National Council for Social Studies, a Dogwood Title by the Missouri Associations of School Librarians, as well as longlisted for the Green Earth Book Award, and more. He has written for The Boston Globe, Essence, Huffington Post, AdWeek, and Cosmopolitan, and won both the Letter Review Poetry prize and a Letter Review Essay prize.

Joseph’s writing and philanthropic work go hand-in-hand, and he has been recognized for community investment by Forbes 30 Under 30, the Comic-Con Humanitarian of the Year award, The Root100 list of Most Influential African Americans, and was most recently honored with the 2023 Malcolm X and Dr. Betty Shabazz Vanguard Award, as well as the 2024 Allyship Award at Lincoln Center’s Black Girl Magic Ball. He has been a featured speaker at the UN HeForShe Summit, and has worked with fortune 500 companies and presidential candidates on their DEI efforts.