Notes on the People the World Refuses to Hold

won’t somebody wrap the Black boy in a yes,

drape him in a sky that don’t flinch at his shadow—

ain’t there an amen shaped like arms for him?

I watched Magazine Dreams on an afternoon when the noise was already too loud in my head. The kind of day where the hum of everything around you feels like an old song you forgot the words to, and the ache behind your eyes won’t sit still. It was one of those days where your body shows up, but your spirit is still arguing with ghosts.

I didn’t watch the film for clarity. I didn’t expect answers. I just wanted a little darkness, a cool room, something bigger than me flickering on the screen.

But some stories don’t begin. They seep in. Like water under the door. Like breath when you thought you were done crying. Magazine Dreams is one of those stories.

It’s a film that begs the question: What happens when the world doesn’t just misunderstand you, but builds itself to unmake you?

And it doesn’t ask rhetorically. It demands you see firsthand.

This movie reminded me of the way a boy has been taught to say he’s fine but doesn’t meet your eyes. The way a Black man jogs through a neighborhood that used to feel like home, only to find every window watching, every sidewalk folding in on itself. The way everyone calls me “strong” and I want to scream, because I know that’s just a pretty word for being denied softness. For being denied help.

Magazine Dreams isn’t about bodybuilding. Not really. It’s about the way a man becomes muscle so no one can see him falling apart. It’s about silence dressed up as discipline. About rage stitched into skin. It’s about Killian Maddox, yes—but also about every Black boy who learned early that if you cry too loud, you disappear faster.

I don’t know what kind of essay this is yet. A prayer maybe. A eulogy for something we never got to name. Or maybe it’s just a mirror I’m too tired to avoid tonight.

Either way, I’m writing it down so I don’t forget what the world tried to erase.

To truly unpack Magazine Dreams, I must begin not with the film itself, but with the day that carried me to it. Because this film didn’t simply speak to me—it saw me. It saw so many of us. The kind of seeing that feels almost impolite in how precise it is. The kind that presses its fingers against the bruises you thought you had long hidden.

That day began with me having lunch with my mother. It was our first time seeing one another in roughly four years, the two of us had been separated by trauma, confusion, silence, ego, and a dull ache neither of us could name before. We sat in a restaurant near Columbus Circle, eating overpriced food, dancing carefully around old wounds and new questions, neither one quite meeting the other’s eyes.

When lunch ended, I was supposed to meet my friend, Damarcus, at Magic Johnson Theater in Harlem to see the film, but I knew I couldn’t rush straight there. I knew I needed space to breathe, to uncoil, to ground myself in what had just happened.

The older I’ve become, the more I’ve acquired various tools—small rituals, moments carved out of ordinary days—to reclaim myself. One of those tools is walking. Something about the rhythmic fall of footsteps on pavement gives me back a quiet authority over my body. It’s a ritual I may have picked up from my dear brother, Robert Jones, Jr., as he has mastered the art of walking ungodly distances in an attempt to find his center.

And so I walked, beginning at Columbus Circle, 59th Street, moving north towards 125th Street, in Harlem.

The walk, at first, wasn’t any more interesting than any other walk through New York City. The sidewalks held their usual chorus of foot traffic, murmured phone calls, impatient honks from unseen cars. I was on the phone with a friend, recounting the surreal nature of seeing my mother again—unpacking how her voice still managed to sound like home and exile all at once. We were caught somewhere between laughter and ache, the way friends do when navigating hurt.

And then my phone died.

There was no poetry in the moment—just silence. The kind of silence that feels a little heavier than usual when you’re alone in your thoughts, unsure what time it is, and vaguely aware that you’re supposed to be meeting someone for a film that starts soon. Even though you don’t know what soon is, because you have no semblance of what time it is.

So I kept walking, slowly at first, thinking I might catch a store or a sign or something to anchor myself to the time. Eventually, needing to know for sure, I spotted a small café on the Upper West Side and decided to ask the two women standing outside—one Asian, one Black—if either of them had the time.

When I walked up, they both looked startled, as if I had interrupted something sacred. The Black woman’s eyes narrowed, and with a tone that felt almost accusatory, she asked, “Don’t you have a phone?”

I smiled gently. “Not at the moment. It died a little while ago.”

There was a beat of silence between them. They looked at me, then looked at each other. A kind of shared calculation passed between them, and then the Black woman said, “No, sorry. We don’t have the time.”

I nodded. “Okay, thank you,” I said, and kept walking.

But the encounter clung to me like smoke. It wasn’t the denial of information that hurt—I’ve gone without far more important things than the time. It was the quiet suggestion that I was suspect, that my presence required explanation. That even in a moment as mundane as asking for the time, I might be read as danger.

I thought about asking someone else, but all I saw ahead were white families—strollers and sunglasses and that leisurely, protected pace I’ve never known. And so I didn’t press my luck. I walked, uncertain of the time still. Then, as I neared Columbia University, I figured it must be nearing the movie’s start time, so I began to run. My dress boots weren’t made for running, but I ran nonetheless.

As my legs carried me through Harlem, sweat trickled down my forehead, pooling at the edges of my jacket. By the time I reached 123rd Street and Morningside Avenue, just two blocks away from the theater, my breath came in ragged intervals. I was delighted to relax as the light at the intersection changed from red to green.

Delighted, until I suddenly saw a police car rolling toward me with that slow, deliberate crawl that every Black person recognizes—less an inquiry, more a warning.

The window rolled down, and a young white officer leaned slightly out, eyes sweeping over me from head to toe, lingering long enough to remind me that in his gaze I was not fully human but something to be assessed, measured, managed.

“Everything alright?” he asked, voice laced with a practiced politeness that always seemed poised between threat and concern.

“Yeah,” I said curtly, annoyed in a way born of accumulated indignities. A lifetime of encounters like these had honed my ability to answer without provocation, careful not to let my annoyance show too clearly—because annoyance, I’ve learned, is a right not afforded to people who look like me.

They looked at me for another silent second, their faces unreadable behind dark glasses, then drove slowly away. As they departed, I stood there considering how long they might have been following me, how long the slow, invisible sirens had sounded around me without my knowing. Who, I wondered, had potentially placed the call about a Black man running in dress boots and a lunch outfit through Harlem in the afternoon? Who had looked at me and decided my presence was enough of a disruption to merit attention?

I walked the rest of the way to the theater, steps heavy, heart heavier still. Until I finally made it—with minutes to spare.

By the time I met my friend, and we found our seats in the theater, the world had already reminded me what it means to move through it in this body.

I sat there, breath still unsteady, jacket damp with sweat, trying to disappear into the hush of the dark. And there he was—Killian Maddox. A man whose body looked like armor, but whose eyes betrayed a kind of ruin I recognized instantly.

Before I go further, I want to say this—because I know someone will ask why I haven’t already.

Jonathan Majors, the actor who plays Killian Maddox, has been accused of abuse. The allegations are serious. The conversations around him are necessary. I do not write this essay to excuse or explain him.

But I also do not write this essay about him.

This is about what the film, in its broken brilliance, reveals about the world that made Killian—and what it asks us to reckon with about how we treat Black men who are breaking, who have already broken, who were never allowed to bend in the first place.

The art is complicated. So is the artist. But what the film knows—deeply, hauntingly—is that systems don’t wait for a verdict before they begin the erasure. That’s the part I cannot look away from.

The film opens with stillness—a kind of waiting room hush. Killian sits across from a psychologist, a white woman with kind eyes and practiced concern. He is there, we understand, because he has lashed out. He is there because the system requires it—because his aggression, real or perceived, must be managed. He is there, in other words, not to be understood, but to be contained.

Killian is a bodybuilder, a man sculpted in grief and desperation, all discipline and hurt pressed into the shape of muscle. And yet in this moment, seated in that room, he is small. Not in size—his body still takes up space—but in posture, in voice. He begins to speak, slowly, about food. About how the food in his neighborhood is killing him. About how there’s nothing fresh, nothing good. Just sugar and grease and salt. Just slow poison dressed as convenience. So he has to drive miles away to another neighborhood for quality food.

“I think they do it on purpose.”

It is not a rant. It is not incoherent. It is the kind of truth we’ve been taught will be met with apprehension. But it’s truth nonetheless.

And then we watch her face.

She listens, or at least appears to. But something shifts. The way her eyes narrow just slightly, the way her pen stops moving. It’s a look I know well. It’s the look people give when they’ve decided your truth sounds too much like a conspiracy theory. When your clarity reads as delusion. When the world you’ve lived—every corner store with a fried food glow, every stomachache mistaken for hunger—feels too far from their world to be real.

She doesn’t really challenge him. She doesn’t have to. Her simple question does the work.

“Who is they?”

And you can feel, even in those early minutes, that he knows it. That Killian knows he is being heard but not believed.

I recognized that look. I had just come from a day shaped by those very same shadows—where asking the time made me a threat, where running to a theater turned me into a potential suspect, where simply moving through the city in a Black body became its own kind of transgression. Killian’s moment in that office wasn’t an isolated scene. It was a mirror. A man tries to explain how his world is killing him, and the listener—the system—offers a smile instead of a lifeline.

That’s the trap, always. To name the system is to be labeled paranoid. To fight back is to be called angry. To try to survive it is to be told you’re making excuses. Killian spoke about food, yes—but what he was really saying was I am being starved of care, of nourishment, of humanity. And the woman across from him, with all her degrees and quiet sympathy, responded the way the world so often does: Are you sure?

It is clear—achingly clear—that Killian is not well. The film never names it, never hands over a diagnosis. And I am not a clinician, so I won’t pretend to know what clinical box he might be placed in. What I do know is that there is something beneath the surface of this man that trembles, that shifts like an earthquake you can’t quite see but feel in the walls. The clues are there—in the cadence of his speech, in the way his eyes seem to hover just behind the moment, as though always chasing something far off.

At one point, Killian tells another character about his mother and father, and their tragic demise, which I won’t give away. And so Killian lives with his grandfather, Paw Paw, a Vietnam veteran who seems to know—instinctively, mournfully—that the world will not make room for his grandson’s hurt, condition, or Black manhood. It will not cradle it. It will not understand it. The best he can do is try to give him tools to survive it.

Focus. Workout. Work hard. Don’t complain. Don’t think anyone will give you shit.

There’s something quietly devastating about the way Paw Paw has to offer Killian regimen to keep him alive. These are not lessons in hope. They’re instructions for how to stay alive when he is out in the world. They’re similar lessons to what my uncles used to teach me, during the rare seasons they showed up—slipping into my life like wind through a cracked window, then slipping out again. Do your pushups. Read a book. Stay focused. Don’t let these motherfuckers think they can walk all over you.

A guide for survival, not salvation.

So Killian takes all that advice—Paw Paw’s old wisdom, the world’s silent expectations—and does what so many of us have been taught to do when the soul is breaking: he builds the body.

He becomes a bodybuilder. Not out of vanity. Not for leisure. But as an act of translation. Because in a country that cannot, or will not, hold the soft grief of a Black man, perhaps it might hold the hard discipline of one. He builds the muscle not simply to be strong, but to be unbreakable, to become the very thing this nation demands of him—impenetrable, stoic, invulnerable. The muscle is not the story. It is the armor.

I have known many Killians. Boys who learned early that their worth would be measured not by what they carried emotionally, but by how much they could carry physically. I have been told, like them, that strength was survival. That vulnerability was a threat. That to bend was to risk breaking in full view of those who would not help you put yourself back together. We are told to work out before we are told to speak up. We are handed weight sets before we are handed the language for our sadness. As a younger man, I was part Killian.

Maybe I still am.

Killian’s body is his offering. He sculpts it like scripture. He sacrifices for it—blood, money, dignity, health. And for what? For a shot at being seen. For the chance to become a version of his idol, Brad Vanderhorn, a white man whose muscles are praised not as armor, but as beauty. Whose fame is not cautionary, but aspirational. Vanderhorn is adored. Killian is devoured.

The difference is not just in skin. It is in the mythologies that this country assigns. A white bodybuilder becomes the emblem of discipline, of greatness. A Black bodybuilder becomes a curiosity at best, a threat at worst. Killian’s dream is not delusion—it is a mirror. He has seen what is rewarded and tried to mimic it. But mimicry will not save him. Not when the world refuses to see his body as anything but excessive, grotesque, dangerous—or still lacking.

He posts videos of his workouts, tries to go viral, tries to be noticed. And the internet, like the world, laughs at or scrolls past his pain. Or worse, engages with his effort and social awkwardness in a heartbreaking manner. Commenting on his videos with things such as, “Why doesn’t he just kill himself.”

Killian reads these comments, and you can tell they devastate him, but he carries on.

This is what happens when a Black man’s last hope is visibility. When he has been ignored for so long, he begins to believe that the only way to matter is to become a monument to suffering. And so Killian builds and builds and builds. But no amount of muscle can quiet the noise in his mind. No regimen can erase the systemic violence.

No six-pack can substitute for a touch that says, “You are safe.”

Throughout Magazine Dreams, Killian endures violence in nearly every form imaginable: emotional, economic, physical, spiritual, sexual—violences layered into the daily calculus of his existence, each inflicted by a society that feigns innocence even as it leaves bruises. Most often, these violences come at the hands of white people—people he cares for, or those he has merely sought respect from. They see him clearly enough to wound him, yet never fully enough to care.

He tries to outwork this violence, as Black men often do, believing that discipline might protect him against cruelty. But no regimen, no diet, no level of perfectionism can shield him from these assaults on his humanity. Killian’s unraveling is not immediate or sudden—it is a slow erosion, a patient dismantling of his sense of self. It is what happens when the world commits harm and calls it fair, inflicts pain and labels it just, until the victim himself begins to doubt reality. Until he starts to wonder if the violence is, in fact, his fault.

In America, gaslighting is not just psychological abuse; it is structural. The nation’s foundational lie, after all, is that the enslaved deserved their chains, that the colonized invited their oppression. This lie still breathes, whispering into the ears of men like Killian Maddox, telling them that they are dangerous, threatening, irrational—that their fear is misplaced, their anger unjustified, their hurt illegitimate.

Throughout the film, Killian’s mental health declines. Not because he is flawed, but precisely because the society around him functions exactly as designed. The film refuses to pathologize him as a monster, but neither does it offer salvation. It forces viewers to witness his dissolution without providing comfort or redemption. We watch as he grapples with reality, fighting battles in his mind that no one around him recognizes or respects. We see him reach out, again and again, only to grasp empty air.

Watching Killian, I was reminded of Bigger Thomas, from Richard Wright’s Native Son—another Black man who the world misunderstood at best, demonized at worst. Wright crafted Bigger as a warning, a mirror held up to a society that refuses to acknowledge its complicity in creating his rage and despair. Bigger didn’t become violent because he was inherently monstrous; violence became his language because all other tongues had been taken from him. Like Bigger, Killian’s story is not of a monster—it is of a man desperately trying to be human in a world that refuses his humanity.

And the more Killian unravels, the more he is watched.

He is watched at his job, where every social misstep is another nail in the coffin of his employment. Watched at the therapist’s office, where his truth is not engaged but assessed, his pain treated as performance. Watched on the internet, where his pleas for connection and recognition are met with ridicule and silence. And he is watched by law enforcement, whose eyes patrol the contours of his body not as a site of suffering, but as a possible crime scene.

This is surveillance not simply in the literal sense, but as an ethic, a climate. A thing so constant it becomes air.

I thought of this when the cop car slowed beside me that day in Harlem. When I felt the crawl of authority in the way one feels a chill before the rain. I was in dress boots, running—not from anyone, not toward danger—but still, that was enough. I knew what they saw: a Black man in motion. And in America, a Black man in motion is never neutral. He is advancing, escaping, invading—always moving wrong.

Killian is never allowed to simply be. His rage is not grief, it is threat. His silence is not sadness, it is defiance. His confusion is not the result of trauma, but an indication of danger. These symptoms, which would be medicalized—gently explored—in white men, are criminalized in Black ones. We are not patients. We are profiles.

To be a Black man like Killian, like me, is to perform two simultaneous acts: the act of surviving the daily hazards of white supremacy, and the act of appearing safe enough to survive it. This is the dual performance—exhausting and unrelenting. You must carry the unbearable weight and smile through it. You must bleed internally and walk straight. You must be harmed and never show it.

And so, we come to what Magazine Dreams reveals without sentimentality: the impossibility of rest.

Killian never gets rest. Other than his Paw Paw, he never gets to fall into someone’s arms, unjudged. He never gets the kind of tenderness that says, you don’t have to fight here. No one in the film tells him, “I believe you.” Not really. Not when it counts.

This is the epidemic within the epidemic: the denial of softness for Black men. We are told to be strong, to take it, to man up. But what is manhood if it requires the burial of your own humanity? What is strength if it means you must carry it all alone?

I have known this denial intimately. I’ve felt it in my spine, where the tension never quite lets go. I’ve felt it in my sleep, or the lack of it—in the hours spent lying awake, rehearsing the next day’s performance. I’ve felt it in the quiet moments when I wanted to cry and instead clenched my jaw. Because I was told—explicitly and implicitly—that we do not get to fall apart. That the world only tolerates our sorrow once it has become spectacle or statistic.

So what is the cost?

What is the cost of living in a world where a Black man can only cry when it’s too late? When the tears are no longer inconvenient because the body has stopped breathing?

The cost is Killian Maddox. The cost is all the boys and men like him, who build armor until it breaks them. The cost is me, sitting in that theater seat, my breath still catching from the run, from the sirens behind my eyes, watching a man fall apart not because he was weak—but because he was never given a place to rest.

There is a difference between falling and being pushed. Between a downfall and a deathtrap. Killian Maddox didn’t simply fall. He was built for rupture. His neighborhood fed him grease and sugar. His doctors gave him side-eyes instead of diagnoses. His bosses called him unstable while stealing his labor and smile. His country sculpted his silence into suspicion and then demanded he explain himself. What we witness isn’t collapse. It’s architecture.

The film shows what happens when every system in a Black man’s life colludes against his breath.

Killian’s story isn’t fantasy. It’s documentation. A dispatch from the frontlines of a war so old we forget to name it. I’ve seen Killian’s face in schools, in courtrooms, in hospitals, in the mirror. I’ve read about him on coroner reports. I’ve sat next to him on trains where no one meets his eyes. I’ve buried him.

Which is why, when the credits rolled, I didn’t clap. I didn’t move at first. Just sat there thinking of my mother’s voice, the weight of the officer’s gaze, the sound of my own footsteps running uptown in dress boots. I thought of Killian. I thought of the boys I love. I thought of the men I consider brothers. I thought of how little separates us from him. A moment. A policy. A misunderstanding. A bad Wednesday.

I walked out the theater differently that evening.

The city was the same. The sirens still impatient. The corners still cracked. But something in me had shifted. Not loudly. Just enough. Like a window left open before a storm.

This is not just a story about a man. It’s a prayer. A warning. A mirror.

And I suppose this is my prayer, too—

For Killian, for myself,

For all the boys not yet undone:

Let the world flinch before our shadows,

Let someone say yes before the breaking,

Let us live long enough to cry and be held.

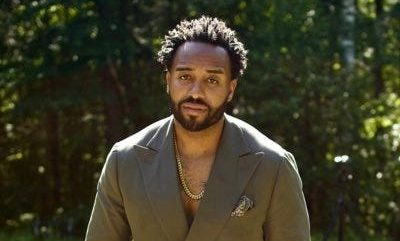

Frederick Joseph is a Yonkers, NY raised two-time New York Times and USA Today bestselling author. His books include a poetry collection, We Alive, Beloved, two books of nonfiction, Patriarchy Blues, and The Black Friend, a collaboration, Better Than We Found It, a children’s book, The Courage to Dream, Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, and the forthcoming Kirkus and Publisher’s Weekly Starred reviewed YA novel, This Thing of Ours.

His work is available on Substack.