By Allen R. Gray

NDG Contributing Writer

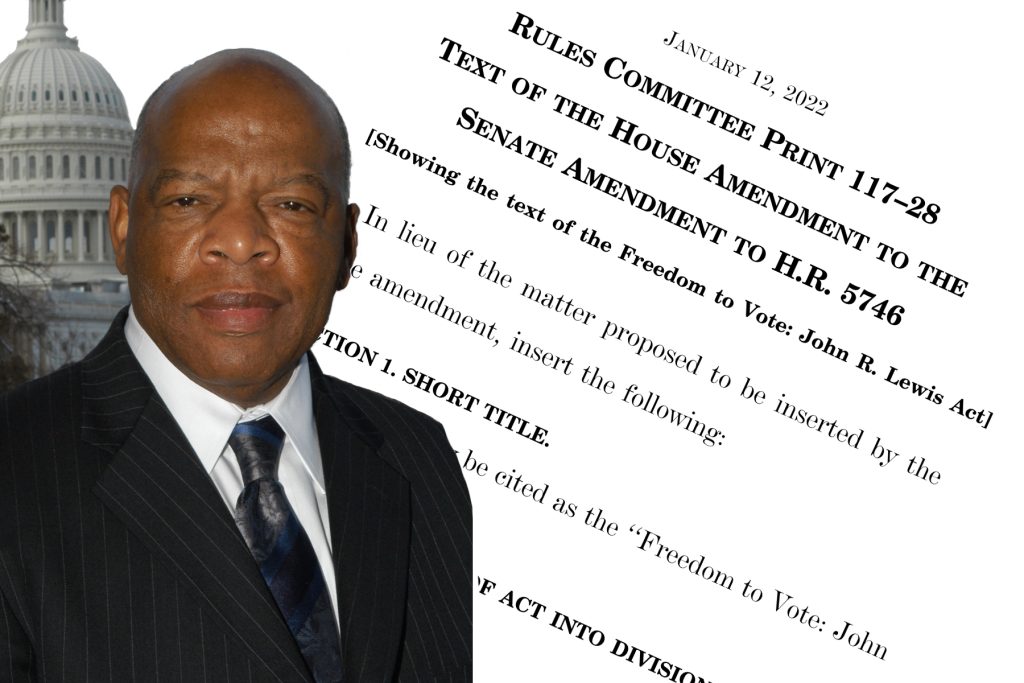

John Lewis is no longer with us that he may offer a pound of flesh, like a young Lewis did on Bloody Sunday, to preserve and make whole the most critical piece of our American democracy—a citizen’s right to vote unabated. The John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act is a measure that seeks to give teeth to the government’s ability to respond to contemporary voting discrimination.

So why, then, is there such great debate over the passing of the Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act?

The one hundred years following emancipation and Reconstruction saw Blacks as that one enumerated group that was affected the most by voter discrimination. So, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 Act sought specifically to undo the wrongs perpetrated against Black voters—and to directly address those states that were the chief prognosticators of that wrongdoing.

The right to vote unabated is where the blurred line between voters’ rights and a state’s right to alter those rights collide. The contention hovers around one’s inalienable rights under the constitution. The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments protect every person’s right to due process of law and person’s right to vote unabridged or be denied due to “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” The Tenth Amendment reserves all rights not granted to the federal government to the individual states; and Article Four of the Constitution guarantees the right of self-government for each state, thereby creating a loophole. That meant that states that might seek to hinder voter rights could change voting procedures as they see fit. The Act of 1965 sought to close that legal loophole.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was enacted to combat the discrimination Blacks were experiencing at the ballot box. Section 5 of the 1965 Act restricts “eligible” voting districts from making changes to their voting procedures and election laws without first gaining official authorization from the U.S. Attorney General or a three-judge panel of a Washington, D.C. district court. Section 4(b) of the 1965 Act describes eligible districts as those that had a voting test in place as of November 1, 1964, and less than 50% turnout for the 1964 presidential election. Districts meeting the formula must then prove that the proposed changes “neither has the purpose nor will have the effect” of negatively impacting any individual’s right to vote based on race or minority status. Section 5 was originally enacted for five years, although, it has been continually renewed since that time and stood until 2013 when the constitutionality of the Act was challenged in Alabama.

In April 2010, Shelby County, Alabama took its opposition to Section 5 to a federal court in Washington, DC, challenging the Act’s constitutionality in the landmark case Shelby v Holder. In September 2011, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia upheld the constitutionality of Section 5; then in May 2012, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of the Columbia Circuit agreed Section 5 carried constitutional merit. Shelby Cunty appealed that ruling to the Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the case in November 2012.

NDG 1/13: MLK Family asks for no celebration until lawmakers pass voting rights legislation

On June 25, 2013, a conservative dominated Supreme Court ruled in favor of Shelby County. The Court ruled that the coverage formula in Section 4(b)—which determines which voting districts are susceptible to Section 5—is unconstitutional because the formula used to determine those jurisdictions is outdated. Thus, the unconstitutionality of Section 4(b) rendered Section 5 inoperable (until Congress enacts a new coverage formula).

Armed with the Supreme Court’s decision on Shelby, states boldly instituted discriminatory changes to voting practices that made the voting process a much more arduous endeavor for disenfranchised people of color and numerous other enumerated groups of citizens.

The Lewis Act seeks to reestablish the authoritative might of the 1965 Voting Rights Act to prevent states from enacting random and discriminating laws and procedures that would allow a state to manipulate and control elections by alienating voters from the polls.

In its 2013 decision, the Supreme Court left open a proviso recommending that Congress create a new formula. The Lewis Act seeks to fulfill that stipulation and restore the protections that the 1965 Voting Rights Act originally intended by:

• Modernizing the Section 4(b) formula to establish which states and localities have a pattern of discrimination

• Ensuring that voters are not adversely affected by preventing last-minute voting changes and requiring that officials publicly announce proposed voting changes at least 180 days before an election, and

• The Lewis Act will expand the government’s authority to send federal observers to any jurisdiction where there may be a substantial risk of discrimination on an election day.

Currently, the Lewis Act was introduced in the House of Representatives on August 17, 2021and passed on August 24, 2021, by a vote of 219-212.

The Act was then introduced to an evenly divided Senate on October 5, 2021, where the fate of the Act might fall prey to filibusters, clotures, and dependency on a 60-40 vote.

On November 3, 2021, the Senate took a procedural vote on whether to open debate on the Lewis Act. Defiant and contentious Republicans blocked the Lewis Act from advancing by a vote of 50-49. Although one Republican, GOP Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, did vote with Democrats, it requires at least 10 Republicans to join with all 50 Democratic Senators for the legislation to advance.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer thanked Murkowski for her support of the right but had stern criticism for the rest of the Senate Republicans.

“I thank (Murkowski) for working with us in good faith on this bill,” he said, “but where is the rest of the party of Lincoln? Down to the last member, the rest of the Republican conference has refused to engage, refused to debate, refused to acknowledge that our country faces a serious threat to democracy.”

Schumer said, “just because Republicans will not join us doesn’t mean Democrats will stop fighting,” and went on to say they will work to “find an alternative path forward, even if it means going at it alone to defend the most fundamental liberty we have as citizens.”